Let’s take up a loose thread from the earlier post, “Judges Jump to Conclusions.” In the recording and Dimanche Gras performance of “What’s Wrong With Me?” Shadow pulls out an old and familiar bone of contention from under his hat. But by 2000 he had sharpened this bone to a spike:

They took all my music,

Disguised it as Soca,

Deprived me of credit,

Which I owned as I suffered.

Few Calypso aficionados take this perennial claim of Shadow’s seriously. There are two versions of the Soca creation story and one of them has ossified into an uncontestable tablet.

The prevailing orthodoxy confidently maintains that Lord Shorty invented a music called “Sokah” around 1973, evidenced in his single “Indrani.” The narrative, and part of the apologetics, of this creation story come from Shorty himself. He described his intentional innovation of what many musicians of the early ‘70s passively characterised as the ‘dying art form of Calypso.’[1] Shorty set out to cross-fertilize the essential Afro-Caribbean structure of Calypso (albeit with no shortage of Spanish, French and Celtic melodies in the mix) with the rhythms and, in the case of “Indrani” and several other later compositions (including “Om Shanti Om”), Indian-inspired melodies as well. This was a stroke of genius on his part, and was something, arguably, only a Trinbagonian could do given the size and cultural import of the South Asian demographic in this birthplace of Calypso.

Thus from (1) a vexed concern about the impending “death” of Calypso, (2) a heady inspiration to unite chief musical genres of Trinidad & Tobago, and (3) the convenient opportunity (or providence) of being able to reach for these traditions within himself as a native of strongly Afro-Indo Princes Town in southern Trinidad, Lord Shorty genetically engineered a new music. He called the music “Sokah,” with the prefix “So” representing “the soul of calypso” and the “kah” representing “the Indian influence in the music.”[2]

Now this latter reference to “kah” has always been a bit mysterious to me because Shorty never tells us what “kah” means so much as what it connotes for him. When pressed on this cryptic “Indian thing” in “kah” he offered that “kah” is the “first letter of the Indian alphabet” (in fact it is the first consonant of the Devanagari system, which you often learn after you’ve learned how to write your vowels). So we can match the “So” that is Calypso’s “soul” to the “beginning” that’s suggested by “kah” to denote a new direction, a new soul, a reincarnation, if you will, of Calypso music.[3] It is precisely because of Shorty’s philosophical description (augmented by other musicians, journalists and scholars), and perhaps more importantly, his naming of Sokah, that he is given credit for inventing this music. And what a music it became!

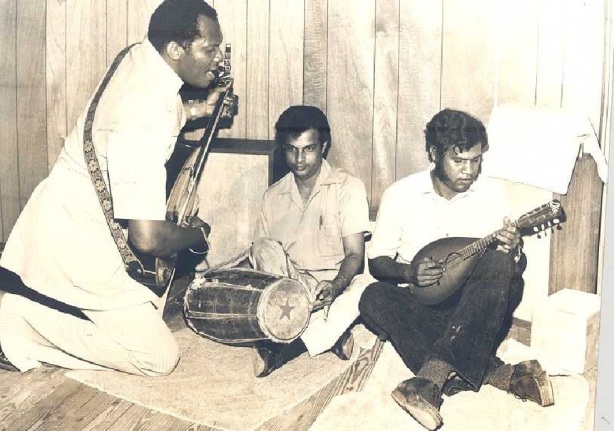

Lord Shorty (later Ras Shorty) with Robin Ramjitsingh and Bisram Moonilal, early 1970s

Image from the brilliant folks at Zocalo Poets

(http://zocalopoets.com/2014/02/28/kaiso-calypso-soca-pepper-it-tt-style/)

This new Sokah music was as exciting as it was controversial. Calypso purists seemed content to watch Calypso die pure (which it never was, what with musicians from Roaring Lion to Kitchener having often laced it with Jazz and Classical music) than witness this Frankensteinian resuscitation by dhantals, dholaks and other Indian instruments seemingly patched together with the European and African ones already in use. Inversely, some Indo-Trinidadians were unsettled and offended by the mischievous and lascivious description of the female protagonist in Sokah’s flagship song, “Indrani” and felt this Afro-Trinidadian, Shorty, was belittling “their” women and by extension the Indian musical traditions he was referencing in the tune. But musicians had taken notice of Shorty’s new sound.

For its part you could call the troublesome new music a hybrid, because hybrids are simply the product of mixture but cannot themselves produce offspring. If you want another hybrid like the one you’ve produced, you have to create a new one from similar ingredients and mix them from scratch. This Sokah was a hybrid, not a new species. Inspired people have continued to make the same kind of hybrid all the way up to contemporary masters like Mungal Patasar and Pantar, and some Soca-Chutney composers, mixing similar Afro-Indo ingredients from scratch and getting their own hybrids. One might say that even Shorty himself was attempting a second Sokah hybrid from scratch, when he seems to have come up with something else. After his 1974 album ,The Love Man, received harsh criticism for his continued use of Indo-Caribbean innovations (complex musical structures that were also stressing out his musicians), he dropped the Indian instruments themselves, replaced them with Western ones, but kept the Indian-inspired rhythms and melodies they had been playing. The yet newer sound on only some of the songs from his 1975 album Endless Vibration was a strikingly international sound, somewhat akin to the Afrobeat we could hear from Osibisa and Manu Dibango, but still unmistakably West Indian.

Although songs like “Om Shanti Om” (from the 1978 Soca Explosion album) would revisit the earlier Afro-Indo musical experiments of “Indrani,” much of the new sounds on Endless Vibrations and the following 1976 album Sweet Music were not those of the hybrid formula Shorty first called “Sokah.” Now the music was a funky, disco-oriented music that journalists themselves had to come up with an explanation for. It was writers listening to this new international dance music who reinterpreted the meaning of the word “Sokah” and changed it’s spelling to “Soca”—the “So” kept to mean “Soul” (which was what Trinis called Rhythm & Blues and Funk music collectively) and “ca” simply designating Calypso. The new funky Calypso sound and it’s name were interpreted, reinterpreted, or as Shorty sometimes insisted, misinterpreted, as a combination of American Soul music and Calypso.

Complicating the situation further was the fact that in 1977 Shorty himself put out a super funky album with an enormous crew, and with him talking in a quasi-American accent (part of a monologue style popular among R&B artists of the time). The tremendously influential album was called Sokah: the Soul of Calypso and its name, while making no reference to Indo-Trinidadian music (or the mixture or mélange of T&T musics supposedly at the heart of Sokah) referenced instead the precise two components that journalists had identified as the two main ones in the new music: “Soul” and “Calypso.” And by 1978, Shorty had abandoned his “Sokah” spelling and, seeming to say ‘oh to hell with it,’ called his 1978 album Soca Explosion. On that album, again, he returned to the Indo-Afro-Caribbean formula of “Indrani” in “Om Shanti Om” and “Come with Me” but in other songs like the irresistible and savage attack on Dr. Williams, “Money is No Problem” and the psalm-like challenge to Reggae’s Rastafarian, bible-quoting dominance of the airwaves “Who God Bless,” the international Afrobeat style continued to reformulate the meaning of the word “Soca.”

It seems that while Shorty was still figuring out the exciting thing he was doing, how he should describe it, and what he should call it journalists and indeed the public were making some decisions of their own. Soca for them was a crossbreed of Soul and Calypso, Indian music optional.

It was this international Afro-Disco Calypso that inspired Maestro, Merchant, Lord Nelson, Black Stalin and even seduced Kitchener out of his traditionalist watchtower. This “Soca” was not a hybrid. It was a new species, able to reproduce in the minds and studios of dozens of Calypsonians. Even Kitchener’s and Sparrow’s! The prominent bass-lines and lyrical, often staccato horns blowing in unison were joined by spacey-sounding synthesizers, organs and other electronic instruments. People happily crowned Shorty the inventor of this music, tracing it right back to him, even though they had essentially discarded his definition and his name for the music. Soca was the new music of Trinidad & Tobago and indeed the Caribbean, with Antigua’s Short Shirt and Montserrat’s Arrow among the major disciples and descendants blossoming across the Lesser Antilles, all mastering the new funky arrangements.

After Maestro’s sudden death in an auto accident in 1977, grieving fans called for his recognition as a co-author of Soca, introducing the second tablet of Soca’s otherwise monolithic history. But Shorty himself recounted his friend Maestro’s original skepticism about “Sokah,” which he says did not alleviate until the Indian rhythms and melodies were finally being played on Western instruments. Only then, says Shorty, was Maestro eager to copy his arrangements, employ some of his crew and even use some of the same vocalisations on songs like his 1976 “Savage.”[4] Indeed you can sing entire phrases from “Savage” along with the tune of Shorty’s “Sweet Music” of the same year but the melodies and horn arrangements are quite different installments in the same genre.

The disagreement over whether Maestro helped invent Soca partially stems from the popular, and somewhat justified, tendency to trace the new music back not to 1973, the year of “Indrani,” but back to 1976, the year that both Shorty and Maestro came out with records that were almost entirely the new funky Afrobeat Calypso—the former with the album Sweet Music and the latter releasing the album Maestro ’76 and the 12-inch (or “disco”) single “Savage.” To boot, the following year, Shorty and his Vibrations International orchestra released the aforementioned Sokah: Soul of Calypso, featuring the exegetical song, “Vibrations Groove” in which the musicians systematically assemble a Soca tune one part at a time, demonstrating what “Socah” is, a la Soul singer King Curtis’ “Memphis Soul Stew” of 1967. And the same year, 1977, Maestro releases an album entitled Anatomy of Soca in which he defends the new genre saying that music can’t be made “for the old folks all de time” (in the song “Soca Music”).

If you’re a Shorty exponent, you see Maestro swooping in and reaping the benefits of three years of experimentation by Shorty. If you are a Maestro advocate, you see those three years as prologue to an essentially simultaneous invention by two musical geniuses, one that may have been inevitable anyway, given the importance of R&B and Funk in Trinidad “blocko parties” of the time.

And in the midst of this controversy stroll the Shadow watchers who contest this whole linear chronology. They bid us to recall where Shadow was and what he was doing during this whole “invention of Soca” period. What was Shadow doing in 1973-1976 exactly? What is the foundation of Shadow’s claim to Soca? Why does he seem to describe Shorty as a Johnny-come-lately to the new music in his song “Dat Soca Boat”?

…He said he is de Soca king

[That] I can’t make with de Soca king

I call de mental hospital

“Come quick to avoid a funeral”

A man came in my house to beat me

He came in my house to fight me

I belong to de house of music

He is either crazy or real sick

But I don’t want to sink dat Soca boat

(Chorus: I don’t want to sink dat Soca boat)

Just don’t want to sink dat Soca boat

(Chorus: I don’t want to sink dat Soca boat)

I doin’ my own thing

Don’t know why they molesting

I am musically ‘sick’

Mummy beat me with music stick

If I tackle de Soca

De boat might turn over

(“Dat Soca Boat” from If I Coulda, I Woulda, I Shoulda, 1979)

Is Shadow’s claim completely groundless? Is the battle for the watershed of Soca threatening to become a Battle Royale?

Now follow this carefully:

(1) if what makes Shorty’s and Maestro’s music “Soca” is more so the cross-pollination of “SO-ul” and CA-lypso (and not Shorty’s Indo-Caribbean instrumentation that mostly goes missing by 1976), and

(2) if what makes “Soul” music itself what it was to Trinis at that time in the 1970s (i.e., Funk), which was characterised by the pioneering decision to put the bass on top of the rest of the music, essentially having it play rhythm and melody at the same time, and

(3) if this unprecedented melodic bass-line is precisely what Shadow did with “Bassman” back in 1974, then hadn’t Shadow fused Soul and Calypso in 1974, not 1976?

And add this:

If Shadow is universally praised for his originality, if not his downright strangeness, and as journalists such as Bukka Renie (2000) have declared “he copies no one”[5] and yet his musical oeuvre is considered “Soca” today, then what is Soca exactly? Is Soca what we have been defining it as, according to Shorty, who took 3-4 years to define it before Maestro walked away with part of it?

When exactly did Shadow join Soca’s ranks so seamlessly by just being himself? Or maybe we should ask, “when did Soca come and join Shadow’s programme (‘already in progress’) so seamlessly that when we look back on Shadow’s career we call it all “Soca”? Because we do indeed see Shadow as both a Calypso and a Soca artiste going all the way back to that weird, infectious song with the walking bass-line and lightning-fast staccato horn bursts, called “Bassman.”

Put yet another way: if Soca came and met Shadow “doing his own thing,” encompassed Shadow’s music seamlessly, and neither Soca nor Shadow were completely transformed or overthrown by the encounter, can Shadow be described as having ‘adopted’ Soca or did Soca adopt Shadow? Perhaps we should consider whether the category of Soca itself was not expanded by Shadow.

And what of Shadow doing the same thing to Calypso what Funk did to Rhythm & Blues? Don’t Shadow and Art De Coteau hone in on that bass-line, turn it into melody and rhythm at the same time and put it front and centre in the music (which we hear musicians doing in the aforementioned “Memphis Soul Stew,” in which we witness Funk trying to break away from R&B)?[6] It is true that Shadow and De Coteau didn’t reevaluate and elevate the drum kit in the same way as Funk does, but neither does Shorty or Maestro.

So Shadow didn’t just put a little bit of Superfly in his Calypso (i.e., he didn’t just adopt Funk as a flavour), he fundamentally changed Calypso’s use of bass (and horns) by reevaluating Calypso’s structure in much the same way that Funk reevaluated R&B’s. Shadow adopted the mechanics of the Funk revolution rather than simply importing/adopting its finished products.

If we insist upon the orthodoxy that places Lord Shorty (and secondarily, Maestro) at the watershed of Soca between 1973 and 1976, and for sake of simplicity exclude Shadow and Calypso/Soca arranger extraordinaire Art de Coteau with their early 1970s experiments with melodic bass lines, Sci-Fi-sounding synthesizers and those rapid-fire, staccato brass arrangements, Shadow still remains a masterful innovator and precursor of the 1976 So-Ca (i.e., Soul & Calypso) phenomenon. In the end, the 1973 Sokah of “Indrani” is not the funky, Osibisa-esque Soca of 1976-1982, which swings back and forth like a pendulum between the hectic abandon of the Disco dance floor (e.g., Maestro’s “Bionic Man” of 1976) and the theatrical grandeur of a blaxploitation soundtrack (e.g., Black Stalin’s “Vampire Year” of 1981). And we cannot deny that starting in his 1973-1974 studio recordings Shadow and Art De Coteau pioneered an experimentation with Calypso that became part of the history of that same funky music other people called Soca. Art De Coteau, after all, arranged for several of the Soca giants. We can also observe that this Soca confluence happened without Shadow needing to make any adjustments to his steady programme of innovation during that period.

We might see Shadow’s music as a branch of Calypso that punched a separate and earlier hole in the perimeter of that category, not far from the hole through which the new species, Soca, would sprout later in 1976. Maybe Shadow’s innovation and Shorty’s weren’t exactly the same but today, after virtually everyone has tried their hand at Soca, it is hard to tell the two legacies apart.

If you think I am being unnecessarily harsh on what I must call ‘the runway narrative of Shorty’s creation of Soca,’ my contestation is not of Shorty’s account of events nearly as much as it is a rejection of the way Caribbean scholars construct history. Our former colonial masters have taught us a history that is essentially a story of wars and great men—processes, women and the Global South be damned.

If you read any history of, say, the gingerbread house, a fascinating example of the cosmopolitan nature of our Trinbagonian and Caribbean culture, you will swear that a Scotsman, George Brown, was responsible for the whole phenomenon of openwork architecture, in Trinidad at least. Countless Indo-Trinis installing Mughal-inspired openwork jalis (transoms) in their houses (like the ones at Lion House in Chaguanas), numberless Africans building porches around their houses, and the British and French Orientalist adoption of Chinese pavilions bringing those to Trinidad, Haiti and Martinique are not nearly as interesting as the biographical story of a man, George Brown, who ‘revolutionized’ the architecture of Port-of-Spain with his mechanical fretsaw. All those Africans, Indians and Chinese (and even a fair number of Frenchmen and Spaniards too) are subsumed beneath the billowing trouser legs of one George Brown, a fella who basically edited and selected from a vocabulary assembled by thousands of nameless masters before him. The stories of steel bands, firms, trade unions, political parties and indeed the whole nation of the Republic of Trinidad & Tobago are told (and taught) in much the same way.

This is “Great Man” history. And this is the history we tell of Shorty and Soca. It is the kind of history that Shorty and Shadow themselves grew up with so they too have entertained contentious views of their roles in Soca history.

Shadow has also entertained us with several Calypsos on this controversy, including the two mentioned in this post.

I for one love to watch a thing “begin” because it is trying to watch something “begin” that you realize there is never a precise beginning moment at all. The microscopic, sub-atomic grain of a process as it unfolds renders a “beginning” more like a shorthand designation of a general time and place than like a hard truth. And as Western scientists and Western religions argue over how the universe “began,” I am always struck by their tacit assumption that a beginning is a very real thing, rather than a quaint, somewhat ethnic, literary device that gets a story going.

I am still looking for the “beginning” that holds up to analysis. The creation of Soca is one such contested beginning, with Shadow a little earlier than or simultaneous with Shorty depending on who you ask, and with Maestro arriving just as the DJ turns up the speakers in the blocko party. Everyone else seems to arrive at the party to find the three of them already there…diggin’ Rhythm & “Blues in [their] shiny shoes.”

Endnotes

[1] Rudolph Ottley, Calypsonians from Then to Now vol. 1 (Arima: Book Masters, 1995), 63-64.

[2] Jocelyn Guilbault, Governing Sound (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2007), 173-174; Rudolph Ottley, Calypsonians from Then to Now, 65.

[3] Jocelyn Guilbault, Governing Sound, 173. In fact, the explanation Shorty gave Guilbault when she asked him in 1997 about the significance of the latter half of this “Sokah” spelling is the fullest I’ve found in the sources I’ve located.

[4] Rudolph Ottley, Calypsonians from Then to Now vol. 1, 74.

[5] Bukka Renie, “Shadow’s Lament: Am I Ugly?” (http://www.trinicenter.com/BukkaRennie/2000/Mar/Shadowslament.html)

[6] Circa the mid to late 1960s was when pioneers like James Brown finally made an entirely new genre out of the increasingly clarified “Funk” category. See http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Funk

I stumbled upon these: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xoYM97IqrNk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gpLUUlX39ZE and wondered if there’s any merit—even fleeting—to Eddy Grant’s claim though it was dismissed out of hand by Chalkie and Shorty. In rejecting the ‘great man’ theory of history do we stop at three with respect to the ‘invention’ of soca?

LikeLiked by 1 person

My Trini prejudice is to dismiss Eddie Grant’s claim too. But why? My whole point is that it is impossible to pin down the exact beginning of a thing. To the namer have gone the spoils, but certainly more people than Shorty (and let me stress Art DeCoteau here) contributed to the birth of that musical phenomenon. Soca is music, it’s not a Model A by Ford (and Ford had thousands of inventors to thank anyway). Soca is an organic thing and it is my opinion that Shadow punched the hole in the ‘Calypso boat’ through which Shorty flooded with a music and a sophisticated syncretic vision that HE named, “Sokah”…but by Maestro’s Savage (when Shorty himself says he backs off of the music) the music is no longer “Sokah” to Shorty himself and so by his own stringent, somewhat exclusivist criteria, the music of Savage, Bionic and Sugar Bum Bum is not exactly his (certainly not in content [in Shorty’s own opinion], but neither in structure).

LikeLike

Yes, while I agree with you that it’s hard to ‘pin down the exact beginning of a thing’ I wonder if this stance doesn’t leave the window wide open. For years I have been hearing the claim that King Wellington with his “Steel and Brass” (1973) must be viewed as an early and key player in soca’s evolution. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3r06CnXMgeY&spfreload=10). One also wonders if Kalyan (‘What we gonna do next?’ LP, 1975, and later ‘Trini Vibes” 1977) should not be in the runnings (if not coterminous with Shorty’s and Shadow’s claims). Interestingly, too, while Shorty and Shadow (later Eddy Grant) directly and/or indirectly broached the issue of ‘invention’, the music of the other aspirants reverberates as their bones contestation. Accepting the view that the late 1960s to early 1970s was a period of great turmoil throughout the society, art/music not being exempted, there was much cross-fertilization from within and outside the body politic creating a very dynamic and fluid time musically and beyond.

Still, an aversion to the single inventor school is borne out by the distancing from the notion of Spree Simon being pan’s singular inventor. Our penchant for privileging a single source—not too different from what Best referred to, in the political sphere, as the dangers of (a single story) doctor politics– is reflected in the claim by many in the 1970s that Nearlin Taitt, a Trini, was the inventor of “rock steady.” (see http://caribbean-beat.com/issue-93/secret-hero-jamaican-music#axzz3NIsXGprU).

LikeLiked by 2 people

Your phrase “the late 1960s to early 1970s was a period of great turmoil throughout the society, art/music” gets to the heart of this period of innovation and “cross-fertilization” in which dozens contributed to the greenhouse atmosphere in which certain key characters managed to breed a new and fruitful species called Soca. We can give Shorty his due but some orthodoxies will object to us giving Shadow (and others) credit as well, especially as more than an “also ran”…Great Man history is awfully convenient and expedient (with room only for Darwin but not Wallace, Edison but not Tesla) and when anybody challenges monolithic history (note my phallic symbolism), there are expenses involved in changing all those official records: monetary publishing expenses; credential expenses; social capital expenses…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. One must not forget the whole narrative of Trinidad being a “Dougla” nation. Sokah, for many, represents an artistic marriage/fusion of the two dominant cultures on the island. Indians can claim sokah as “we ting” too, unlike pan, which is pretty much an all Afro Trini invention. Finally, I would pull Ed Watson in as one of the creators.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I definitely see Ed Watson in the mix back in those exciting days. And it is precisely because of where in Trinidad Shorty himself is from that we can find his Afro-Indo (i.e., dougla) narrative credible and compelling, if not singular and monolithic as AN origin of Soca.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Soca was invented and then defined by Shorty and the main musician who backed Shorty in his early soca recordings was Ed Watson and not Art De Coteau.

Art De Coteau was happy to work on Shadow’s “Bass man” in 1974 because it was still basically a calypso with a traditional calypso beat but a modernized bass line in certain sections of the song.

In the very same year 1974 Art De Coteau was not happy working on Shorty’s “Endless Vibrations” mainly because of the total change in the beat in Shorty’s song which is why Art De Coteau refused to finish arranging the song and Ed Watson had to be hired by Shorty to complete arrangements on “Endless Vibrations”.

Art De Coteau resistant to soca when Shorty when Shorty was introducing it which is why Shorty had to turn to Ed Watson and Pelham Goddard to a lesser extent.

The main difference between calypso and soca was the introduction of the new beat and it was not just the bassline changes that made soca different to calypso.

I will add more on this to explain later but Shorty did what he did first and the others followed.

Ed Watson and Pelham Goddard were also very important to the establishment of Soca much more so than Art De Coteau who was initially against soca music was.

It was only because he worked with Shadow why Art De Coteau eventually got won over to join the soca bandwagon.

LikeLike

While this post begins with an absolute and dogmatic statement about an act of ‘invention’, it provides some interesting biographical insights into De Coteau’s thinking circa 1974. Socapro, would you mind telling us where you learned these details so we might expand our research, even if it is from the personal experience of having been there on the spot as it were.

My next question is if, as you say, it is working with Shadow that won a stubborn (i.e., Soca-intransigent or Soca-resistant) De Coteau over to Soca, then at what point did Shadow become an exponent of Soca (as to begin De Coateau’s conversion)? And what effected/affected Shadow’s ‘conversion’?

Pendant to these questions are the following:

If Bass Man is essentially a Calypso with only some minor (and uninfluential?) manipulations of the role of the bass, what other Calypsoes from the time, or before (not after, I guess, since soon afterwards Shadow would be playing Soca) are comparable to this composition? (i.e., in terms of the rhythms and other musical structures you mention)

and

If not Bass Man, what would you say is Shadow’s first Soca composition?

LikeLike

As a keen observer of soca’s evolution, I wonder where Nearlin Taitt falls into the equation as I think he was listed as one of the arrangers on Shorty’s “Endless Vibrations” LP. Interestingly too, I just stumbled upon an article from the Sunday Express of March 13, 1994 in which Kim Johnson, in assessing Shadow’s work, writes:

“The emphasis on heavy bass rhythms makes Shadow more a progenitor of soca than anyone else, Shorty included. For the main ingredient that distinguishes soca from calypso isn’t any particular rhythm: there are many different rhythms in soca, such as the Baptist rhythms in Superblue’s music, or the Indian rhythms in Shorty’s. Rather, it’s the dominance of the bass lines which separated soca from calypso and which makes Shadow’s music particularly in tune with today’s youth, who have been so influenced by reggae and dub.”

Indeed, “Bones of Contention on the Soca Boat” is ah borse title to spark, guide, and facilitate this discussion! Respect….

LikeLike

Kim Johnson’s assertion is more bombastic than anything I’ve offered regarding Shadow’s place in the lineage but Johnson is a respected voice on the history of many things, including our music. And a prominent voice like Johnson’s making this assertion indicates just how young, unstable and controversial the Soca mythos is (is Cro Cro singing about the Soca controversy in 1979 when he says “Shadow start it, Maestro push it”? https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VJx9x3DzpaA).

MY aim on the other hand has not been to fire salvos on behalf of the Shadow camp but rather to question the dogma of the prevailing origin narrative of Soca, which seems to omit Shadow entirely, and I feel I am doing this in the spirit of Shadow’s own lyrical ‘questioning of everything.’

Wen people ready to cuss jus’ because yuh raise de question, that is when you know you should be raising the question.

LikeLike

@Lawrence Waldron:

I actually interviewed both Shorty and Ed Watson in 1992 when I was carrying out most of my soca research to establish exactly who did what on the important recordings. I visited Shorty and his family in Piparo that year as well as Ed Watson at his home in Carenage and interviewed both of them.

By 1992 I had already collected most of Shorty’s and Ed Watson’s albums so I had a good idea of who played on the different recording from the album information but decided I needed to interview both Shorty and Ed Watson when I realized that they were the two main people who played on all the important early soca recordings.

I interviewed Shorty first and he explained to me why he used two arrangers Art De Coteau and Ed Watson on his first major soca hit “Endless Vibrations”. Shorty explained that Art De Coteau didn’t want to play and arrange the music in the modern style that he wanted and it was causing them a lot of argument in the studio. So Shorty hired Ed Watson to complete arrangements on the track but most of the musicians who played on “Endless Vibrations” were from Art DeCoteau’s band. Shorty had worked with Ed Watson and His Brass Circle on his previous album the “Love Man” as well as on “Indrani” so Ed Watson was the natural person for him to call on if Art DeCoteau was not happy to give him what he wanted with the musical arrangement.

Shorty also mentioned that his good friend Maestro had a similar problem with Art DeCoteau when he decided to follow in Shorty’s footsteps and champion Soca. Even though Maestro used Art DeCoteau to back and arrange all the tracks on his 1976 album “Fiery” Maestro decided to use Pelham Goddard to arrange the soca tracks on his early 1977 album “Rampage” album while using Art DeCoteau to arrange the remaining uptempo calypso tracks on the very same album.

When I interviewed Ed Watson in 1992 at his home in Carenage a few days after interviewing Shorty in Piparo, Ed Watson confirmed what Shorty had said about finishing off the arrangements on “Endless Vibrations” because Shorty and Art DeCoteau had fallen out over what he was trying to do with the music and beat in “Endless Vibrations”. Of course the rest his history as “Endless Vibrations” went on to become the first soca smash in T&T 1975 carnival season and even cause ripples in New York..

Regards to Shadow all his tracks between Bass man in 1974 and his “Dreadness” album in 1977 were calypso/soca hybrids with Shadows trademark rolling bass lines in sections of the tune but all contained the traditional calypso beat, However on Shadow’s 1978 album “De Zess Man” he included two tracks that featured the new soca beat that Shorty had been regularly featuring in his music from 1973 when he had his hit “Indrani”.

Here is a link to listen to one of them (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FYHpD0E3CgE). Most of the other songs on Shadow’s 1978 still featured the traditional calypso beat.

Between 1977 and 1978 was the period when soca began to take off in a big way and most of the other artists and musicians who were initially hesitant decided to jump onto the soca bandwagon. 1978 was the year that Kitchener scored with his massive hit “Sugar Bum Bum” with the help of Ed Watson and Pelham Goddard.

Regards your final question, it would be wrong to say that Shadow’s rolling bass lines from his 1974 “Bass man” hit onwards were not influential as it clearly was. However the music was generally changing in T&T during the early 1970’s due partly to the conscious mental changes brought about by the Black Power Movement in addition to new studio recording technology that was allowing musicians and artists to produce as well as to arrange their music. The drastic improvements in studio recording technology in the 1970’s was naturally allowing the rhythm and bass lines in calypso studio recordings to come out much more clearly than was the case in the previous decade.

Here is a very similar song (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KOoHSgaPlBI) structure wise to “Bass Man” from King Wellington with a traditional calypso beat but with a funkier heavier bassline in sections of the song that is also from 1974.

And here is Shorty’s “Soul Calypso music” recorded in 1972 (https://soundcloud.com/socapro/soul-calypso-music-lord-shorty). Take a listen to the heavier and more soulful style bass line yet again.

Kitchener also did a track with a two-note soca style bass line in sections of the song in 1973 called “One To Hang” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nSG_ga4Cbqw). Recording quality is not that great but you can still follow the more modern bass line pattern. So as you can hear the music was already going thru a natural change when Shadow’s “Bass Man” came along in 1974 but of course Shadow’s song still had a major impact as it won the road march.

LikeLike

I read Socapro’s post here with great interest. He has evidently put in some serious work talking to makers of the music and has provided a lot of supporting links to help illustrate his point. At one point I thought he was getting close to settling the matter with a corroborated story about Art De Coteau’s initial resistance to Soca. I was actually quaking and excited at the same time in that way that some scholars and other people who don’t mind getting their minds blown can appreciate: fear, curiosity, anticipation. The post made me realize how much research (including fieldwork) I have yet to do to talk on Socapro’s level about several parts of the music.

But by the end of the post, there was no comparable interview with Shadow or Art De Coteau – so we were only getting one side of the story. And while there were many knowing and seemingly qualified statements made about Soca, there seemed to be a common conflation of Indrani with other, later forms of Afro-soul-sounding Soca. While I insist on very few things on this blog, I must insist that Indrani is NOT the same kind of music as, say, Money is No Problem. And finally the recurring reference to the “beat” that differentiates Soca from Calypso leaves me (and us) faced with a serious problem that unless solved will lead to endless arguments and endless negative vibrations (hahah) over the prospective originators of this Soca genre.

What is the problem? It is a problem that some people don’t want to solve because they feel it might limit the free development of Soca. The problem is “How do we define Soca?” or perhaps more fundamentally, “What is Soca?”

Because even Shorty put out records where he slowly builds a Soca tune and tells us ‘this is what Soca is’ but then he would point back at something he did before and tell us “that was Soca too” or play something different later and call that Soca as well. An undefined music is one that we will never stop arguing over: the beat, the chords, the instrumentation, etc.

The Cubans don’t have this problem. Compared to us they have their musics defined to within the millimeter; from Changui to Montuno to Mambo. But I understand why we have a distaste for defining our music too taxonomically. We don’t want to kill it. This is why while others lament that we cannot seem to settle on one standard way of tuning a pan, I am weary of that sentiment because standardization could limit the ongoing development of the instrument. But on the other hand, we have judges sitting there in the days leading up to Carnival, set up to judge the quality of a medium that is so unclearly defined…how can you judge what has not been defined? How do you know you aren’t skipping some requisites and/or ignoring some parameters?

So here I am: back to wondering how Soca came and met Shadow already in progress and yet somehow between Bass Man and Zess Man (according to Socapro) his music changed from Calypso to something Shorty invented (even though you can sing 1975’s Shift your Carcass to the first two tracks on 1978’s bona fide “Soca” album Zess Man). And while Shadow’s music remained so unique throughout the age of Soca’s incubation and birth (i.e., the 1970s) that you always knew it was him, that same music (that remained so very unlike Maestro’s and Shorty’s) still came to be known as Soca.

It seems to me that Shadow either contributed to the yet uncertain definition of Soca, or he expanded the category now known as Soca (while it was still in its cradle) without getting any credit for it…

LikeLike

@Lawrence Waldron:

Regards your quote:

It seems to me that Shadow either contributed to the yet uncertain definition of Soca, or he expanded the category now known as Soca (while it was still in its cradle) without getting any credit for it…

I mostly agree with your statement minus the last part about Shadow not getting any credit for what he did. Shadow got credit for what he did because his music is so unique and always stood out especially during the 1970’s when he worked with Art De Coteau who was also a top notch bass player.

At one point in the 1980’s Shadow tried to brand his unique soca style as Shadi Wadi Riddims but the branding did not catch stick.

But as I have pointed out from a structural perspective Shadow music was dominated by the traditional calypso beat until through most of the 1970’s and he did not start to use the soca beat in his music until 1978. The music of Shorty and all the other’s who followed his formula was dominated by the new soca beat especially after 1978 when Kitch’s “Sugar Bum Bum” that features the soca beat that Shorty introduced became a major hit.

I must also add that a lot of the older calypsonians were initially resistant to totally abandoning the traditional calypso beat in their music and so many of them did a lot of calypso/soca hybrid songs in the 1970’s. Their music was basically structure like a traditional calypso in certain sections and like the new soca music in other sections.

I think that hybrid calypso/soca style allowed the older singers who were reluctant to abandon Calypso which they loved and to get a balance that they were comfortable with but also let to some confusion for listeners in trying to decide whether to describe those songs as a calypso or a soca. I just call them what they which is a calypso/soca hybrids.

Here is an example of a calypso/soca hybrid track from Kitchener and there were many similar hybrid tracks during the 1970’s. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kh81HPZbcGY)

The problem that we have is that everyone took the name that Shorty created for his music and used it to describe what they were doing. However though working with the likes of Ed Watson and Pelham Goddard most of the others were accurately able to adopt the main changes that Shorty introduce and use it as standard elements in their own soca music.

Btw I meet Shadow on a number of occasions at calypso shows he performed at but it was not convenient at the time to try to interview him. However I don’t think I actually need to interview Shadow to find out anything new because people like Alvin Daniell have done very comprehensive interviews with Shadow (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TWn2S0zhMuE) that told me everything I needed to know outside of what I could already deduce from his music recordings and complimenting album information that that I have been able to collected over the years.

Shadow is indeed a music genius just like Shorty was and it is interesting to note that they were both born the very same year 1941 and in the very same month of October with 2 days of each other.

Best regards

LikeLike

It seems to me that we are doomed to repeat ourselves, overlook parts of what has been said here by others, and simply keep insisting upon our staked positions UNTIL we define both Soca and Calypso, especially in terms of this “beat’ that separates Soca and Calypso.

We would have to do this in a musicological (not rhetorical) fashion so that there will be less room for articles of faith (and other ‘givens’) and more gravity given to musicological structures: beats, backbeats, up-beats, down-beats, on-beats, off-beats, cross-beats, rhythms, counter-rhythms, polyrhythms etc. Then we would probably have to move on to the role of the bass.

We’ve now gone over the same territory several times with examples but few definitions; competing, disproportionately-weighted and unilateral narratives but not much theoretical analysis of beats and bass.

And to arbitrate this debate with anything approaching objectivity, we would have to locate multiple (not singular) musicologists, none of whom have any dog in the localized controversy of Soca’s origins.

Alas, convening an international team of musicological specialists with a complete disinterest in Caribbean music (as to render their pronouncements relatively impartial) is very possible, but ultimately not what’s happening on this webspace.

But it’s been an interesting discussion.

LikeLike

@ merepamphleteer:

Nearlin Taitt is much more of a factor in the Reggae revolution than in the Soca revolution.

Nerlin Taitt left Trinidad with his seven piece band The Nearlin Taitt Orchestra on a tour up the islands to Jamaica in 1962.

They got stranded in Jamaica after not being paid by their tour manager for their Jamaican gigs and Byron Lee helped out members of Nerlin Taitt’s Orchestra by securing them musician jobs in a number of local Jamaican bands. The drummer Aldon Ison was sent to Llans Thelwell and the Celestials band in Mobay, the tenor and keyboard player Carl Griffith went to the Vagabonds at Silver Slipper in Kingston and Nearlin Taitt went to The Shieks.

Most of the members of Taitt’s original band 7 piece band ended up living in Jamaica and a earning money as musicians for a number of years before deciding to either return to Trinidad or to migrate to Canada or England.

Taitt became a major contributor to the evolution of rock steady between 1962 and 1968 recording roughly 2,000 songs most of them which he arranged and became hits. Taitt left Jamaica for Canada in August 1968 to take up another job there.

I believe Lynn Taitt worked on a couple of reggae tracks on Shorty’s “Gone Gone Gone” album which Shorty recorded when he visited Canada in 1972. Shorty had previously known Nerlin Taitt from back in Trinidad where they became good friends while Taitt led and arranged music for the Southern All Stars Steelband of which Shorty was also a member and did some of the band’s musical arrangements as well.

Two of the tracks that were originally on Shorty’s 1972 “Gone Gone Gone” album (“Soul Calypso Music” and “Bajan Gyal”) were also included on Shorty’s 1974 “Endless Vibrations” album so maybe that is why Nerlin Taitt may also have been credited on the “Endless Vibrations” album cover for working on those two particular tracks that were also featured on Shorty’s “Endless Vibrations” album.

I also believe that Nerlin Taitt could also have worked on Shorty’s 1975 crossover album called “Love In The Caribbean” recorded in Trinidad but I need to find my album jacket to double-check. I believe both albums “Gone Gone Gone” and “Love In The Caribbean” contain a couple of reggae tracks that Taitt played on.

Regards Shadow, I think I dealt with what I believe was the significance of his contribution to Soca in my previous post.

LikeLike

Do you have any records of these interviews ? I do believe the technology to document such crucial info existed back in 1992. Also, you keep mentioning this new beat which Lord Shorty introduced and I assume that you are referring to an Afro-Indo so a hybrid. However, as the owner of the blog clearly stated above, the majority of Shorty’s recordings fell under the Afro-soul/disco umbrella. Your continuous attempts to give Shorty sole credit falls flat. “One hand can’t clap.”

LikeLike

My interviews with both soca pioneers (Shorty and Ed Watson) were a series of questions which I wrote down and also wrote down their answers for. Most of the questions that I asked were to confirm or clarify info that was already provided on their albums jackets which I already had copies of.

For example when I asked Shorty about who worked on “Endless Vibrations” he explained that Art De Coteau was not comfortable with what he was trying to do and they fell out so Ed Watson was called in to do the arrangement on “Endless Vibrations” and most of the other tracks on that album.

If you take the trouble to look carefully at the credit details on both the album cover and the vinyl label for Shorty’s “Endless Vibrations” album you will see that it says, Musical Arrangements by Ed Watson. Acc. by Art De Coteau Orch.

When the penny drops you will see why it is wrong to assume that Art De Coteau actually arranged “Endless Vibrations. It was Ed Watson who did the arrangements but since Shorty had already hired members of Art De Coteau’s Orchestra to record the album he still used them as the backing musicians.

Later when I interviewed Ed Watson, he indeed confirmed that it was him who did the arrangements on “Endless Vibrations” but they used Art De Coteau band. So Art did not play an arranger role on “Endless Vibrations” as many folks give him credit for as he was totally anti-soca when Shorty was trying to introduce soca unlike Ed Watson who embraced the change and became the man person alongside Pelham to spread soca around to other musicians and calypsonians in the early soca days.

The fact that Maestro had the same issues with Art De Coteau that Shorty had is also documented on his early 1977 “Rampage” album where you can clearly see that the uptempo calypso tracks were arranged by Art De Coteau but the classic soca tracks “Play Me” and “Soulful Calypso Music” were arranged by Pelham Goddard. If you ever wondered why then now you know. If you have a copy of Maestro’s “Rampage” album on vinyl you can confirm these details yourself by carefully reading the credits info on the album cover.

In addition Pelham Goddard also confirmed that Art De Coteau was initially anti-soca from his comments in this interview (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YHhJux80VOQ). Go to 6:45 and take a listen.

So the logical question is if Art De Coteau was so anti-soca and not happy to arrange both Shorty and Maestro’s soca material up until 1978 then why was he so happy and comfortable working with Shadow between 1974 and 1978?

The answer is quite simple; Art De Coteau did not regarded Shadow’s music as much of a departure from traditional calypso when compared to what both Shorty and Maestro were doing during that same period. Art therefore confirms my observation that before 1978 Shadow was basically doing his own unique brand of calypso with a traditional calypso beat but using his own unique bubbling basslines in sections of the song.

Btw most of the information that Shorty clarified to me in 1992 interview has since been professionally documented in recorded video interviews like this one (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gpLUUlX39ZE) so I don’t really see the need to refer back to my to my original interview notes from 1992 to prove anything new that is not already .

When I refer to the soca beat I am referring to the beat that Shorty developed from his experiments in fusing Calypso with East Indian rhythms like he did in this song (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lRe5gC0VLV4) but without the use of the East Indian instruments. It’s not really rocket science unless you are a bit slow and don’t realise that people can play the same rhythmic pattern on different instruments which can give it a slightly different song.

The soca beat is just the same rhythmic pattern transferred to the drum kit, triangle and guitar in “Endless Vibrations”, “Sweet Music” and other soca tracks that hundreds of other artists copied and followed thereafter while adding their own twist so they all contributed to the establishment of soca a definite distinct music genre separate from Calypso.

Your argument that I give Shorty sole credit for soca is a bogus argument created in your own vivid imagined. Shorty was the first with his soca formula and the others adopted it and spread it from there which is why soca became established as a new music rather than remaining just a novelty experiment style like much of the early stuff that King Wellington did. If no one follows you then it is impossible for you novelty track to grow into a genre like Shorty’s soca clearly did.

Finally I would say that Shadow was one of the few calypsonians who continued to do his own thing and did not outright adopt Shorty’s formula like most of the other calypsonians did. However Shadow still naturally incorporated the soca beat into his music after 1978 onwards simply because the soca beat had become so popular with the majority of musicians. It was inevitable because of the sheer number of calypso musicians who had adopted Shorty’s soca beat and bass line formula by the 1980’s.

LikeLike

[…] has fallen under, although he’s always been an outsider and even this contribution has been overwritten by a confused popular narrative. Bukka Rennie certainly depicts Shadow as an enigma when he writes about him, “He copies no […]

LikeLike

Hi, I posted your article here https://www.facebook.com/groups/448949215244092/?fref=nf as an alternative the Lord Shorty creation narrative. Thanks,

Ken

LikeLike