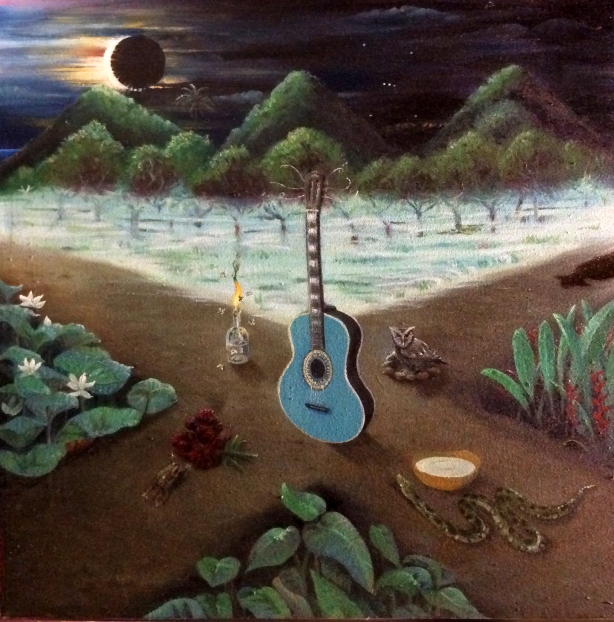

Shadow’s Crossroads, oil on canvas (2011). Lawrence Waldron.

Shadolingo Is Not…

It’s not “too ra loo ra loo ral.”[1] It’s not “de do do do, de da da da.”[2] It’s not a few nonsense syllables repeated as a refrain, to carry a ditty’s melody between verses or across a bridge. It isn’t just to warm up the pipes before the first verse as a Calysponian might with a “lah-da-dee-dai la-la lai lai.” It hasn’t the irrational subject but oft-rational grammar of surrealist cadavre exquis[3] nor does it employ unbroken words, scrambled to surprising effect as in the cut-ups of William Burroughs and David Bowie.[4] Though it’s supremely rhythmic and, potentially, endlessly rambling like the improvised bols of a Hindustani tala, no syllable here is the prescribed name of a specific beat as in several Indian and West African musical traditions. No, these syllables are themselves improvised, sometimes directly on, but often between the wraps on the drum, constituting infectious polyrhythms and multi-layered melodies.

Tom teem tay-tim

Deh-umd tim dom

Tom tim deh-dim

Deh-um dim dom,

Yah!

…Moo dee eh da ma-ow!

Tam dee oh-day-mm,

Tam-tee lai

Tam tee doh yeh,

Tam teem oh-eh,

Ah teem oh-yeh

—Shadow, near the end of “Music Fever,” from the album Music Fever (1981)

“Music Fever,” from the album of the same name (1981)

Woven into and around the music as they are, these rhythmic syllables, dancing in and around the melody of “Music Fever,” might be likened to the carefree utterances of Jazz scat, deep in the groove of the music—like Ella Fitzgerald on the 1951 version of Arnett Cobb’s “Smooth Sailing.”

Dee too-dyun too-you bao

Boo bood-yun boo-yoo bao

Geeby yoot tooden doot duh doot

dat datten-dut duh-doo

Doht too-doo deh

Doo doo det doh dah dah

Ella Fitzgerald’s “Smooth Sailing” (1951). Scat above is transcribed from minutes 1:29 to 1:37.

But resembling the percussive yet tonal beats of African drums and Shadow’s signature basslines more often than the sustained notes of brass and woodwinds (as in scat), giving a syllabic, human voice to those beats and basslines, Shadow’s utterances might just as easily compare to the entranced, rhythmic vocalisations of Spiritual Baptist ‘doption.[5]

Spiritual Baptist practitioners in the process of vocalising ‘doption, Trinidad

These two—scat and ‘doption—are perhaps the closest vocal relatives of Shadow’s inspired para-lyrical improvisations. But are his extemporised syllables just the missing link between them? Is Shadow just scatting in rhythmic tongues?

If they are neither just nonsensical vocal accompaniment nor a strictly codified syllabary, burdened by prescribed tradition, what should we call these idiosyncratic vocalisations? The more of them we hear, over the ever-varying instrumentation of Shadow’s nevertheless unmistakeable musical corpus, the more they seem like the incantations of a lone babalawo at the crossroads, the improvised lingo of a singular initiate in dread musical wizardry. Thus, we might call them, shadolingo.

Spelling it Out

In 2014, when this blog was launched, the decision was made to name it after these mysterious utterances of Shadow’s. But, at the time, the online title was conciliatorily spelt with the “w” in the middle to garner more hits for the young website in general searches for “Shadow.” Additionally, it anticipated the forgetfulness of an infrequent visitor who might misspell it, and not find it in the less clever search engines because they had disregarded that it was a portmanteau (like Buffalypso combines “buffalo” and “Calypso” to make clear that the species is a uniquely Trinidadian breed of thick-skinned water buffalo, or “macoracious,” which combines “macocious” and “voracious” to describe a particularly greedy consumer of other people’s private business). The more intuitive spelling—“Shadowlingo”—has served us well with the increasing popularity of the blog. But it is time to set the record straight with the spelling as originally conceived—shadolingo. It is not just a combination of “Shadow” and “lingo” but a proper fusing of the two terms and two sets of meanings, dispensing with redundant consonants as the musician himself often dispenses with the rational semiotics and structure of English when he merges with the music jumbies and says,

Im tama hoom-day

Am tama-hal

Tim yum tama hoom-day yao!

I-yum tama hal

—Shadow, near the end of “I’m Sick,” from the album Mystical Moods (1984)

The neologism, “shadolingo,” thus reflects the loss of parts of the original in the joining with something else and, in turn, the becoming of something yet greater.

Origins

At the beginning of his recording career, Shadow was already demonstrating an experimental attitude towards the use of his voice. On his first two albums, Bassman (1973) and King from Hell (1974), he can be heard regularly changing speed, volume, and octave mid-verse. His youthful shouting, and especially his use of falsetto for both narrative and musical effect would seldom be heard thereafter.[6] “Dread Wizard” of 1979 is a notable exception for its angry expulsions as befit the album title.

Close observation of Shadow’s singing in those years, and indeed throughout his career, reveals that he is not one for extended notes, even as a master composer of catchy and often haunting melodies. Rather his voice itself has the quality of a tonal drum like a djembe or freshly tightened conga, able to ring a true note but with a warm, dusty shortness and flatness, much smoother than Louis Armstrong but sweeter than Sade. Shadow is a rhythmic singer. Yet, on his first two albums, he stretched his plaintive, masculine voice to its limits, no doubt figuring out what he could and couldn’t do to desirable effect.

In the nursery of ideas that he and Art DeCoteau built from 1973 to ‘74, little can be heard that might be called true shadolingo…except perhaps in his most famous Kaiso, and still his epitomical song to many—“Bassman.” The “Pum pe dim pom” and “tum pe dim pom—pom” in the explosive Road March single imitated and drew attention to the innovative, expressive, guitar-like basslines of Farrel (perhaps we should spell the name of Shadow’s apocryphal musical tormentor as, “Phar-el,” to make him seem more Afro-Asiatic and pre-Christian). But these protomorphic iterations, closely following the sound and rhythm of accompanying instruments, were yet to bloom into full-fledged shadolingo. And even these went on hiatus after “Bassman,” being completely absent from the King from Hell album. Then, suddenly in 1975, they were back, and in the first ten seconds of the album, Constant Jamin’, on the title song:

Wim dim wim pim pim pim

Pim dim wam wam tam-pahm

The protomorphic shadolingo that had the crowds scatting along with “Bassman”‘s refrain, “Pom pe dim pom—pom!”, in the fierce, almost vengeful revelry of 1974 (as people threw off their economic, political, racial and other social worries) had returned! But then, two-thirds of the way through “Constant Jamin’,” something more unexpected happened:

La dey la-lay la-lay la la wo-woy!

Not at all an imitation of the rhythm, melody or even phrasing of the bass or any of the musical instruments, this is the human voice doing what only it can do and riffing over the frantic rhythm of the song. In cutting loose from the grammatical and semantic requisites of language, and even from onomatopoeia of the bass, Shadow’s voice was even more fully inhabiting its role as a musical instrument. His vocals were not just a lyrical delivery system meant to harmonise with the key and tempo of the music; it was in there amongst the other instruments making its own melodies, and its own unique sounds.

You can tune a drum so that it plays “toom toom”, “bup bup” or “bap bap.” A saxophone is melodious but mostly in the “oobeedoobee” range, although, if you play it like, say, Coltrane you can get some unexpected, even frightening squeaks, scratches and squeals out of it. If you want a horn to blare, like “bwah wah na nah wow,” you need a trumpet for that (you can put a plunger over it and change that to “bweh weh neh nehh wewh” or switch between the “wahs” and the “wehs” by opening and closing that mute). And anything with strings, from a guitar to a piano will give you a “ting-a-ling-a-ling.” Some gongs and cymbals can blare like trumpets but most tuned metals, like our magnificent steelpan, but also those dreamy Southeast Asian agongs,[7] can ring like stringed instruments while more fully expressing those low registers around “bong” and “ooong.”

But even in a normal conversation, the human voice can make all of those sounds, plus many others, stringing them all together in the most unexpected ways—hisses stitched through melodious vowels in a forest of consonants peppered by grunts and growls, and pocked by the occasional cutting of the breath, or even a click of the tongue if you’re Myriam Makeba or one of her !Khoisan neighbours from the Kalahari. The human voice is an immense mixed metaphor easily uncoupled from the rules of polite speech and trained singing. And from those first bars on “Constant Jamin’,” Shadow had pushed his voice beyond the regular order of language, singing and/or musical instrumentation. He had invented a new vocal expression…and a new sound.

They say brevity is the soul of wit. So, it is worth considering the irony of a singer, known for his unique wit and keen lyrics that cut to the most profound of truths,[8] inventing what might be called an anti-lyrical sub- or supra-language. We should not take for granted that “Constant Jamin’,” and indeed the whole album is first and foremost about music itself—starting with the title track. Without completely suspending his usual lyrical genius, the Shadow of 1975 shifts his focus to the music itself. Songs like “Grooving Time,” “Carnival is Fete,” and the smash single, “Shift Your Carkass,” all take music and dancing as their topic. Even the quirky “principles” espoused in “Statics” are for learning to live life as if one were learning to play music. The band on this album, members of the Art De Couteau [sic] Orchestra, including the unforgettable but unnamed trombone player[9] on “Statics,” is a lot tighter. They have to be. They are often playing at twice or thrice the speed of the first two Shadow albums—or any Calypso or proto-Soca album of the time. If this record is for dancing to, Shadow is trying to wear we ass out!

So, it was this new, deeper engagement with the music, this reckoning squarely with the new sound he and Art De Coteau had been developing, and this unleashing of his vocalisations so that they might be utterly present in and reactive to the music that brought out the shadolingo. In fact, in the albums to come, almost all of them with these new idiosyncratic vocalisations, we would get the distinct impression that Shadow was not just reacting to the music but riding it. Sometimes he seemed himself to be ridden by the music like a spirit medium under the influence. This is particularly the case when his utterances were made up mostly of inseparable vowels (which frustrate transcription in their lack of structural and rhythmic consonants) or the nasal groaning, rhythmic glottal stops, and grunting deep in his throat and/or chest that remind us of the aforementioned Spiritual Baptists in their ‘doption.

Perhaps the song that most clearly demonstrates that shadolingo was an intentional throwing off of linguistic and musical conventions is “Freedom,” off the De Zess Man album of 1977. Both song and album title give us a glimpse of what was going on in Shadow’s mind the previous and that year. When Trinbagonians say “yuh have a zess,” they are not talking about a zest for life or a certain joie de vivre. They mean you have a jumbie on you; you’re possessed by unseen forces which are pushing you to do things.

Calling himself ‘de Zess Man,’ with a picture on the album cover of him in the studio in front the mic with headphones on tells us that the ‘zess’ in question comes from music. The music will fill us to bursting and propel us forward. And the lyrics of “Freedom” sing of a yearning for release from the corruption, sadness and misery “in this world of man.” Yet half the things that come out of Shadow’s mouth in this song are not lyrics at all but pure, unadulterated shadolingo. The song even begins with a phrase of it that has been turned into a handy refrain and taught to the chorus—“O ah ayeah.” The mixed gender chorus repeats this refrain throughout the song, and a similar utterance will reappear in the 1977 12” single “Shadow Thing” in which Shadow, as both arranger and conductor, instructs the listener how to sing, “Ah-oh a-aah yay” as the remedy to the same oppressive “misery” first shaken off in “Freedom.”

“Freedom,” from the album De Zess Man (1977)

The first “O ah ayeah” in “Freedom” is immediately followed by an unbridled “u-who-o-u-who-u-ayeh-ayeh-ah” (as best it can be transcribed).[10] Shadow’s new language has proven it can be polite leitmotif sung by the chorus, but also rampant improvisation intoned by the Master. And in “Freedom” and “Shadow Thing,” Doctor Shadow prescribes shadolingo as the remedy for despair and depression. Is it just misery, sadness and corruption that shadolingo can cure? Because it seems as if Shadow started singing in this manner out of yet another longing only suggested in the lyrics of “Freedom”—a longing to be free from the psychological and cultural freight of language itself. This is explored further in the section below subtitled “Shadolingo Is.”

The Ancient Future: Shadolingo Across Time

Inspired by the onomatopoeia on “Bassman” (recorded in 1973), then incubating over a period of some eighteen months between Carnival 1974 and late 1975, shadolingo emerged a fully developed countercultural vocal idiom on Constant Jamin’, just in time for the Carnival of 1976. Already made hip to a new scene by “Bassman,” party, carnival and hipster audiences dug what Shadow was putting down. It was Shadow’s own thing and would become part of his unique sound thereafter. It did not appear on every song. In fact, it features prominently on only a third of Shadow’s corpus, including many of his singles. From 1975 to 1985, it helped define Shadow’s style for all posterity. From “Jump Judges Jump” and “Children Ting” (1976) to “Dread Wizard” (1978), “Toe Jam” (1979) and “Music Fever” (1981) to “Obeah” (1982), “Snakes” and “If I Wine I Wine” (1984)—Shadow’s popular songs are inconceivable without it. These lingo-laced singles, like “Tension” (1987), even appear on albums where shadolingo is otherwise conspicuously minimal.

On a cluster of albums directly following the death of Art DeCoteau in the late 1980s, Shadow slowly learns to live without his partner in Trinbago music’s great revolution—Soca. But these late eighties albums, for all their popularity, crisp and professional arrangements by Frankie MacIntosh (with his band, the Equitables), and for all Shadow’s clever and amusing lyrics as always, are not the hair-raising, spiritual mindscape in which shadolingo thrives. In fact, they are veritable shadolingo deserts.

By the early 1990s, Shadow had recovered from a flirtation with American music distributors (see the music video for “Rock Your Body” from the 1986 album Better than Ever), had searched his way through the loss of his closest, most long-time collaborator, and had found his way back to the centre of the crossroads. It was yet another ‘return of the Shadow.’

Wootootoo Vèvè, mixed media on canvas (2011). Lawrence Waldron

Full bars of shadolingo returned with him like evening birdsong, rather than the little snippets of it from the previous four albums (1986’s Better than Ever and Raw Energy, then High Tension and The Monster, from 1987 and 1989 respectively). Yet through much of “Music (Dingolay),” the first track on Winston Bailey is the Shadow (1992), shadolingo seems slow to re-emerge. This might seem surprising since this song is one of Shadow’s most famous and critically acclaimed songs on the topic of music itself, and it is usually on these songs about music that shadolingo makes some of its most powerful appearances.

However, “Dingolay” (as everybody calls it) is packed with exegetical lyrics on the origins, structure, functions, and benefits of music. So, for most of this rhetorical song, Shadow stands firmly in his intellect in order to explain music. In doing so, he does not slip as easily into his patented, and now somewhat out-of-practice, twilight language. The shadolingo that eventually shows up in the last ninety seconds of the over seven-minute-long song is not the imploding self-abandonment of “Music Fever,” the mysterious voice echoing out from the wilderness on the 12” single “Evolution” (1979), the spiralling madman’s rant of “Dread Wizard,” the brooding mutterings of “My Vibes Are Heavy” (1977), or the celebratory exclamations of “My Belief” (1975) and downright joyous, even giddy ones of “Without Love” (1976); it is something smooth and self-assured from an elder shaman, more accustomed to coursing through the higher spheres of music consciousness where there are “no friends or enemies.” The shadolingo magic is back, but in cases like “Dingolay,” it’s different, breezier but front-loaded with shadolingo’s own history, plus Shadow’s personal power and experience.

In yet other cases after its return, the shadolingo is just as heady and bold as it ever was, only now, it’s often accompanied by synthesizers, digital pulses, and programmed electric beats rather than just horns, drumkits, bass and guitar.

Since Shadow was one of the original innovators of electronic instruments in Trinbagonian popular music, he was as comfortable making second and third generation Soca (i.e., comparable to that of Rudder then Bunji respectively) as he was in that revolutionary first generation where Moogs took their place alongside horn sections and electric guitars in the studio recordings of Shorty, Ed Watson, Maestro and Art DeCoteau.

Shadow’s 1990s music sounds like a natural development from the explosion of electronic music that had swept the world for the past two decades, thanks to Roland and Korg keyboards (not to mention those £12,000 Fairlight CMI computers) and Linn drum machines. From Kraftwerk, Giorgio Moroder and Parliament Funkadelic in the heyday of electronic popular music in the north to the plethora of British and U.S. New Wave bands of the 1980s, electronic music was here to stay despite its detractors insisting that a drum track is not “real” drumming, and somewhat naively insisting that a synthesizer would never successfully imitate “real” instruments.

The makers of electronic music themselves might have started out (as did photography over a century earlier) to earnestly imitate the art form they were tacitly threatening to replace, but sitting at the keys of your Jupiter-8 keyboard, you soon realized that this machine could make sounds no acoustic instrument had ever produced, noises even the human voice couldn’t make. Synthesizers could play octaves unavailable on any piano or Hammond organ, notes so high, only rats, bats, and antsy teenagers in rubber bracelets could enjoy them, and so low only elephants and whales could groove. Well, maybe not only pachyderms and cetaceans.

African and African Diaspora people were never in the habit of just listening to music. Feeling music vibrate in your bones and in the hollows of your internal organs, where it makes you shudder and raises your pores has always been part of Black music, so those new low sounds that you can only “hear” with your whole body suited us more than ‘just fine.’ And Soca was always part of that electronic phenomenon. One is only to listen to the first bars of “Bionic” by Maestro or “Action is Tight” by Calypso Rose (both arranged by Pelham Goddard) to hear those Space-Age sounds with which Lee “Scratch” Perry, but also dozens of Soca and Afro-Funk/Afrobeat keyboardists were also fascinated in the 1970s. It’s hard to imagine Osibisa’s 1972 album, Heads, without Trinidadian Robert Bailey’s Moog synthesizer sounds.

By the end of the 1980s, the electronic takeover of Caribbean music in general was nearly inevitable. Shadow, as always, was ahead of that wave. In fact, what had started out as interesting synthesizer accompaniment on 1976’s Dreadnessalbum (punctuating the shadolingo-laced “Carnival Scenery” and masterfully answering the bass in the lingo-less “Don’t”) had become a full-blown electronic obsession by the end of the 1970s. “Something Wrong” of 1978 supersedes the bass player with a low synthesizer noise that sounds like a giant, psychedelic caterpillar dangerously lumbering about some cosmic tree on colossal, suctioned legs. That gwankh-gwangh-gwankh sound is joined by yet another synthesizer playing melody. The echoing, distorted and ultimately, intergalactic sounds of “Evolution,” where even the electric bass guitar sounds like it’s been strained through liquid space and a handful of nebulae before reaching Earth, demonstrate that even the more traditional instruments have been guided by the synthesizer keyboard to a new aesthetic. Instead of the synth copying the other instruments, they are copying it!

Shadow’s cosmic vision—of which shadolingo was a vocal expression—was not hampered but aided by the new electronica. By the time “De Hardis”/“D’ Hardest” came out on the 1980 EP, Wake Up, Shadow was already a master of the new digital sound. But this wasn’t a robotic or emotionally dissociative sound.[11] Rather, on “De Hardis,” a fiddle, of all things, echoes, seemingly down from the heavens, and perfectly harmonises with the spacey keyboards. The previous year, Shadow had done the same thing, combining a flute and synthesizer on “Evolution,” but when he did it with the culturally freighted fiddle, it got everyone’s attention. This particular digital-analogue interface has always fascinated admirers of Shadow’s music. How did he manage to get a fiddle to work in this song?!

The fiddle is associated with various Afro-Celtic and Franco-African folk forms in Trinidad & Tobago, not the urbane Calypso. You heard it on episodes of Best Village, but few would have imagined it having a place in the sophisticated, international sound of Soca. The inclusion of the fiddle is one reason that “De Hardis” is among the most unique in the already incomparable oeuvre of Shadow. Its synergy between what seemed like two musical nemeses, the droning, buzzing, whizzing, chopping sci-fi sounds of the new keyboard (assembled in a sanitized Japanese factory by people in plastic uniforms) and the gliding fiddle that whisked us on its frenetic bow back to fireside jigs and bélés in rural Tobago…except, the electronic echo effect on the fiddle causes it to resemble the rest of the music, which is all synthesized or otherwise distorted through other studio effects. Shadow had dragged that bow and fiddle into the digital future.

But could the primal vocalisations of shadolingo harmonise with Shadow’s new electronic sound like that fiddle had? The exuberant shadolingo uttered before the last verse of “De Hardis” proved that this too was possible. However, Shadow’s aspirational electronic anthem of 1982, “One Love,” a pretty song whose soaring scales presaged those of Alphaville’s “Forever Young” by two years, makes no use of shadolingo. We would have to wait a few years to find out if the primordial shadolingo and the futuristic synths were to become proper bedfellows.

In 1981, Shadow snapped back to acoustics and settled up some business with his bassman, both figuratively and practically. On three of the most bass-heavy albums in his body of work (i.e., 1981’s Music Fever, 1982’s Return of the Shadow, and 1984’s Return of the Bassman in which the man in black squares off once again with his haunting music jumbie, Farrel), shadolingo was rampant. It is a cornerstone of two of Shadow’s funkiest pieces of music—the title song of Music Fever and the satirical “Conscience.” At least half of the songs on the album Return of the Shadow feature it prominently, including the hit single “Obeah.” Most of the album Return of the Bassman is peppered with shadolingo, including the title track, but also “More Music” and the monster single, “Snakes,” in which it is fast, syllabically complex and just as important as the searing, sometimes tragicomic political critique of the P.N.M.[12] party. There is a whole verse of it in the middle of the song! (And half a verse near the end).

“Snakes,” from the album Return of the Bassman (1984)

Then, in 1984, Shadow put out two albums—one, Sweet Sweet Dreams, was an off-season album made on his own (i.e., without Art DeCoteau), and the other, Mystical Moods, for the Carnival season of 1985, back with his faithful collaborator. Both featured prominent use of synthesizer keyboards alongside the electric guitars (including the bass) and acoustic percussion instruments.

Instrumental 12” single of “Together” off the album Sweet Sweet Dreams (1984)

Not unlike the Eurythmics album of a similar name, the album Sweet Sweet Dreamsis a masterpiece of electronic, yet soulful music. The shadolingo on this album is relatively modest, sometimes almost lost in the sound effects (e.g., on “Moon Walking”). But not on “Dreaming.” In the escapist exclamation of “Humayeayh!” and the wistful “Whooanannayao” a moody Shadow revels in his nighttime dreams and daylight reveries of his lover. Rhythmically, the song is as much eighties Soca as late sixties Rocksteady/early Reggae (with those choppy keyboard skanks) but with ascending and descending synthesizers through each chorus that could blend easily into a contemporaneous song by Naked Eyes or O.M.D.[13] Receiving relatively little attention at the time, Sweet Sweet Dreamshas since been re-released as one of Shadow’s cult favourites.[14] Its beauty as a unique gem in the wizard’s crown, but also its importance in completing the foundation for Shadow’s next two decades of music (indeed the second half of his career) are now more fully appreciated and acknowledged.

Enjoy the entire Sweet Sweet Dreams album on YouTube while it lasts. “Dreaming” is the third track at minute 10:50 (“Moon Walking” is at minute 24:00)

While most of the songs on Mystical Moods make surprisingly little use of shadolingo, on the second track,[15] “If I Wine, I Wine,” it’s like the shadolingo jumbie reached up through the ancient earth, through the bones of the entire family tree of life and snatched Shadow by the big toe. It is not just a verse of shadolingo we get here, but half the song. After four coherent and amusing verses on Shadow at a party, first losing control of his female partner and then ultimately himself as they both give in to the music, Shadow’s lyrics themselves finally cut loose of lexical signs and signifiers. Bar after bar of shadolingo falls from his tongue, peeling off the successive layers of our propriety. Our pores raise, our eyelids droop, our toes stop tapping jazzily and instead our heels begin thumping on the floor and shaking the room. Our thoracic vertebrae begin to snap our upper torso back and forth like a whip, until we flop to the ground, “wining like a serpent.” Now we fully grasp the absurdity of the line “I was diggin’ blues in my shiny shoes” because once we give in to this music, it’s not just that we’ve ceased to be an overdressed wallflower; it’s that we don’t want to wear shoes at all, or clothes, or even our corporeal bodies anymore.

I confess that in 1985, I walked out of a party when “If I Wine, I Wine” started playing because that song—especially its shadolingo—‘interferes’ with me to an extent that I don’t allow in public. And on another occasion when I was listening to it on high volume at my home, I spontaneously reached for a towel and draped it over my head to moderate the ‘fever’ that came over me (like breathing into a paper bag to cease hyperventilating). Imagine my shock at the discovery that the cloth they drape over preachers (and James Brown) at those fiery moments is not just for dramatic effect! For me, the song just gets more powerful with age (I still watch myself around it), and since Shadow’s passing, I have felt it almost double in potency like he really has taken up his post in some musical, mystical afterlife and is now wielding that power unencumbered by the weaknesses of the flesh. Then again, it could just be my grief enhancing my sensory experience of this composition. Listen at your own peril.

“If I Wine, I Wine,” from the album Mystical Moods (2004)

Again, we shouldn’t be surprised that the song with the lengthiest spell of shadolingo is one about music and its effects. And here it is, laced through and punctuated by futuristic synthesized sounds. On “I’m Sick,” off the same Mystical Moods album, a quirky song about a musical infection brought from outer space, a synthesizer shadows the electric guitar through most of the song, ratifying shadolingo’s harmony with electronic sounds and its close relationship with ‘music about music.’ The lines, “A musical substance, Of which I have no resistance” also point back to shadolingo as having an enchanted quality that renders the musician (and the listener) powerless to resist—unless they walk out the party or the studio.

“I’m Sick,” from the album Mystical Moods (2004)

The Shadowlingo web space will never fail to sing the praises of Art DeCoteau, one of the greatest and most prolific musical arrangers in the history of Trinidad & Tobago music. Yet it must be pointed out here that Shadow’s boldest experiments with electronic music took place on off-season recordings made under his own direction. The singles, “Something Wrong,” “Evolution,” “De Hardis,” and “One Love,” and the album Sweet Sweet Dreams were all arranged and produced by Shadow himself. It was on these recordings without DeCoteau, that Shadow ultimately gathered together the implements for his next musical journey. At key moments between 1978 and 1984, Shadow pulled himself away from his closest collaborator and, in seclusion, found his new direction. The wizard had to retreat from the courtly company of one of the lords of Kaiso arrangement to fulfil a new vision.

From what has been said already about the Frankie MacIntosh years, it might seem that the death of DeCoteau had a more profound effect on Shadow’s music than his independent jaunts into electronica in the early 1980s. But Shadow and DeCoteau had made Mystical Moods together right after Sweet Sweet Dreams, an album with a rich and sophisticated use of electronic music, and after a stint with Eddie Quarless on Better Than Ever (1986), DeCoteau and Shadow worked together for one more album, Raw Energy (1986), before the former’s death. All three of these mid-eighties albums feature synthesizers and the latter two make prominent use of drum machines with programmed rhythm tracks. Yet the electronica is clearly Shadow’s insistent contribution to the partnership with DeCoteau, the Quarless and MacIntosh. Before any of these albums could be made, Shadow first had to find a place for his voice, his lyrics, his bass-heavy melodies, and his recondite shadolingo on a new musical frontier—electronically generated sounds. And he did this searching under his own aegis.

Yet, just as he had found this new equilibrium between his new vision and his long-time arranger, Art DeCoteau passed away. In the years directly following DeCoteau’s death (1987 to 1992) the shadolingo seemed to go out of him sometimes. This is no fault of Frankie McIntosh, who worked with Shadow for most of that time, and has himself been a formidable arranger and masterful instrumentalist. He just caught Shadow in transition, in a kind of emotional and ideational, and perhaps also spiritual, chrysalis (maybe not quite a crisis). From this cocoon, his music would emerge nearly completely different yet eminently recognisable—from the moment he opened his mouth.

“Music (Dingolay),” from the album Winston Bailey is the Shadow (1992)

The 1992 album Winston Bailey is the Shadow, with Fitz Melo Thomas taking over as musical collaborator, is appropriately named as a reintroduction to the master. The acclaimed composition “Music,” a.k.a. “Dingolay” (after which a future album would be named), first appeared on this album and lays out the new, more electrified sound, the seemingly effortless expertise and the masterful attitude. This was a cooler, more self-assured Shadow, conscious of his own authority, not just amongst the fans who recognised him as a kind of musical sage, but over the history and future direction of his music. Winston Bailey is the Shadow also demonstrated the new balance in his lyrics, which had shifted to match his new self-realisation. In this and the coming albums, his social criticisms would become, on average, less allegorical and more instructive with as much exegesis as examples—they had gone from Old to New Testament, from Puranas to Upanishads—yet just as lyrically clever and amusing.

This is not to say that he entirely abandoned proverbs in favour of prophetic and philosophical sermons. His notorious gift for allegory was at the heart of brilliant singles such as “Soucouyant” (1992). And many of his latter-day compositions reopened dialogue on key early works, effectively depending on them as prologue, preface or primary text. “Survival Road” (1993) returns to “Story of Life” (1973 and 1976) and aspects of “Cook, Curry and Crow” (1979). The interrogation (and self-interrogation) of Shadow’s musical gift in “Musical Me” (2004) strongly recalls that of “My Vibes are Heavy” (1977). As mentioned in an earlier post on Shadowlingo, “Scratch Meh Back” (2000) is essentially a sequel to the cult classic “Aging System” (1984). Likewise, “Long Time Carnival (Pay de Devil)” revisits Bailey’s childhood “long ago in Tobago” in rural Les Coteaux that we know so well from 1973’s “Winston.” In the case of “Poverty is Hell” (1993), Shadow needs no recourse to “Dread Wizard” (1978) because there is always something new to be said about poverty. Both songs are unique, popular hits that rely heavily on Shadow’s prowess as a storyteller, though the elder is told from the subjective, the newer from the objective as befits Shadow’s transition from eccentric shaman to eccentric sage.

With the exception of the “Scratch Meh Back” and “Aging System” couplet, all the songs mentioned in the above paragraph feature shadolingo to one extent or another (“Winston” cannot be considered in fairness because it was composed before Shadow’s discovery of this mode of supra-lyrical expression).

Wrapped in his new sagacious authority, however, Shadow could directly engage with hypocrisy, predation, selfishness, laziness, vanity, shifting fortunes, love, betrayal, and poverty without resorting to oblique and sometimes opaque proverbs. Shadolingo would be an integral part of the new, totally electrified sound with the enhanced exegetical lyrics. On “Music (Dingolay)” the shadolingo is expressive yet effortless as if the greying wizard has the mysterious noumenon at his beck and call. Trailing the verses at different tempos, shadolingo flows in graceful, multicoloured ribbons.

By the time his hit album Dingolay came out in 1993, with Carl “Beaver” Henderson collaborating on the arrangements, Shadow’s electronic music had become more and more enamoured with hard-driving, sometimes Hip Hop-type rhythms in which the drums came up to rival the bass in importance. This development can also be traced back to Sweet Sweet Dreams in the eighties—an album “way way out” and ahead of its time. An abiding interest in Reggae since the aforementioned “Dreaming” (also off Sweet Sweet Dreams) had also become more evident, especially in songs like the reflective “Mother’s Love” (1992), the smooth and eerie “Survival Road” (1993), which sounded like a Caribbean answer to Enigma’s “Sadness” (1990), the halting “Oh, What a Life” (1995) and several others.

No early experiment with the new drum-heavy Soca style is more powerful and successful than the hit single “Poverty is Hell.” The shadolingo here recalls the more fitful, aggressive strains from the seventies—shouted at high decibels with stammered, guttural syllables. Not all of the new shadolingo was breezy and elegant! The topic of the song, as all who sweated to it in crowded clubs and house parties knew, is desperation—desperation as relentless as that beat. The reader doesn’t have to be told that it is our custom in the African Diaspora to make music by which we can prance on the grave of our suffering…at least before the suffering rises again from its temporary inhumation.

“Poverty is Hell,” from the album Dingolay (1993)

The electronic drum-heavy Soca experiment would continue for several albums, shaping a new sound for a new generation of Soca artistes, not least of which was a young fella named Bunji Garlin who was still in school at the time in Arima before he started recording in 1998.[16] A recent obituary article on Shadow in Billboard magazine synopsises Bunji’s opinion of Shadow as, “a direct influence on his development as an artist,” going on to quote Garlin as saying that the singles “Dingolay” and “Stranger” (2001) are “two of the greatest crafted songs by any artist in any genre.”

The pounding drum-and-bass of Shadow’s nineties electro-Soca was not just on the single “Poverty is Hell” but in other songs on the massive fourteen-track album, including the apocalyptic “Judgement Fire” and no more cheery “Miracle” which stylistically hovered somewhere between Soca and the New Jack Swing-type R&B and Hip Hop (think Soul II Soul’s “Back to Life” or the New Jack City soundtrack) that had also been reshaping American Black music. Nowhere is Shadow’s flirtation with this ‘New Jack sound’ more obvious than in his 1995 remake of “Don’t.” This retake on one of his most structurally enigmatic songs (it is a heavy piece of music with vexed lyrics and no chorus) is not just unexpectedly natural-sounding, but, like the original, shockingly good and thus maddeningly short (at less than three minutes)! “Tommy” on the same Shadowmania 1 album as the new “Don’t” makes creative use of this new equivalent of 1970s Afrobeat. And the opening bars of the amusing, elliptical narrative of “Gossiping” and 1997’s “Loner” seem a direct homage to New Jack Swing’s own partial origins in 1980s breakdance music. In a truly international twist, songs like the “Don’t” remake and “Tommy” are one part Soca, one part Al B. Sure! or Arrested Development, and one part Maxi Priest-style global Reggae.

“Gossiping,” from the album Shadowmania, vol. 1 (1995)

Interestingly, David Bowie, sharing Shadow’s fascination with the now-mature New Jack Swing style, was working with Al B. Sure! on the song Black Tie White Noise at the same time that Dingolay was in production. Around the same time, Miles Davis was also working with Easy Mo Bee on his final album, the 1992 Jazz-Hip Hop fusion project, Doo Bop. Hip Hop for its part was also reaching out to Jazz. Guru, from the Hip Hop crew, Gang Starr, released his own Hip Hop-Jazz fusion album, Jazzmatazz vol. 1 not long afterwards in 1993 to be followed by three sequels.

The first half of the nineties was a time of great cross-fertilisation in popular music and Shadow, ever the innovator, was at the forefront of the Trinbagonian module of this global phenomenon. In 1973, he had put the bass on top of the music to give us a proto-morphic Soca. In 1993, he had brought the drum back to the fore (albeit from a drum machine) as the driver of a new kind of rhythm-driven Soca-futurism. It wasn’t just “New Jack Soca.” It was quite distinct from that single branch of its multipronged inspiration (i.e., New Jack Swing) and has outlived that now-dated American subgenre, especially in the perennial “Poverty is Hell.”

In the 1990s, some Calypsonians had started going into the studio and rehashing their greatest hits on synthesizers so they could make a record (and a few dollars) on the cheap without too many musicians. Shadow himself tried this once—on The Best of Shadow vol. 1. The result, as with most other senior Kaisonians was uninteresting, and even painful to listen to. However, throughout the nineties and 2000s, it was more often the case that when Shadow synthesized one of his old hits, it was often with a very different and sometimes, even more powerful new arrangement.

This is one of the perennial differences between a musician and a front man, a Calypsonian and a mere singer/performer. With a musician, the music keeps deepening. And while we can critique almost every one of Shadow’s synthesized remakes of his signature “Bassman” along the same lines as all those cheesy greatest hits by other Calypsonians, the two versions of “Bassman” on 2001’s Just for You album are superb. Why do these remakes of the untouchable, almost un-re-attainable “Bassman” finally work, after two or three previous attempts?

The horns!

In the year 2000, Shadow crossed the final frontier in his musical journey. The expanding complexity in his increasingly electronic instrumentation had reached their apogee in shadolingo-laced, electronic albums like Dingolay (1993). On the unapologetically experimental, shadolingo-heavy Eternal Energy: The Shadi-Wadi Rhythms (1997), Shadow seems to have gone into the studio by himself to push the possibilities of electro-Soca yet further. This album is decidedly stripped down in its sound, but it establishes the complex and hard-driving rhythms that will characterise the albums to follow. Up to Dingolay, Shadow had become used to having as many as six or eight different instruments and/or sounds going at the same time on an average song and after the Shadi-Wadi sound and rhythm experiment, he was ready to go back to that and expand the instrument count even further.

“Ease Up” from the album Eternal Energy: The Shadi-Wadi Rhythms (1997)

Keeping all the Shadi-Wadielectronic sounds, including the sometimes-hectic rhythm tracks, Shadow hired a live drummer, Ron Sylvester. And to all those idiosyncratic synthesized sounds, he added a full horn section. The still-new electric, drum-and-bass-heavy sound was now souped-up on rich (and expensive) acoustics.

Working with real brass was not as ballsy a gamble as it might sound. Some of the favourite sounds produced on synthesizers for popular music are ones that approximate brass, reeds and woodwinds. But part of the fun in those sounds is that they do not mimic these instruments too closely and end up being sounds of their own. When used, however, to replacehorns (as they sometimes are in those corny greatest hits remakes), they sound jokey and juvenile like music from a cartoon. This is why previous remakes of “Bassman” like on 1998’s The Best of Shadow vol. 1 had failed. They had attempted to replace horns with digital facsimiles.

But now, real horns were back, and it is worth considering that the elevation of the bass in Shadow’s archetypal, original “Bassman” back in 1974 was only half of its success; the other half was its expert, rapid-fire, staccato horns that ended with that TAT-tada-DAAH like some superhero theme music—but a stylish one like 1960s Batman; not 1980s He-Man! The expert horns on 2000’s Am I Sweet or What? were played by David Jacob and Philo Neptune, under the glorious return of Frankie MacIntosh as arranger. On the following albums, Just for You (2001), Goumangala (2001 for 2002), Fully Loaded (2004), Sound of My Soul (2005) and Enjoy Your Life (2007) these horn players were either joined or replaced by Roger Jagessar and Michael Lindsay, Curtis Lewis, plus Patrick Spicer, Pedro Lezama, David Phillip, and Ancil Daniel. Am I Sweet or What? drummer, Ron Sylvester, was replaced on Just for You and going forward by Sonilal Samaroo.

“Goumangala,” from the album of the same name (2001)

The new, multidimensional sound rumbled low in the basslines. Under Shadow’s, Fitz Melo’s and “Beaver” Henderson’s arrangements, the horns were crisp and tight, blaring like the best at Brassorama. Samaroo was hitting those drums like they were hardened children he caught ‘breakin’ biche’! They thumped, boomed and cracked like thunderclouds. The synths droned, twinkled, whistled, hissed and wheezed like a space ship passing through the rings and atmosphere of Saturn. The music hit you on all octaves. If you didn’t think Shadow could come any more sophisticated than Dingolay, he was surprising you once again. How could this music be so different and still be so Shadow?

Back to the Beyond: Shadolingo Is…

And if I doh want to dance,

He does have meh in a trance

—“Bassman” from the album The Bassman (1973)

With all this music in my soul,

Beyond my control

—“Musical Me” from the album Fully Loaded (2004)

Shadolingo can be traced across nearly the entire arc of Shadow’s career but do we know what it is and what it is doing?

From its sound and function in Shadow’s music, it is obvious that Shadolingo is improvised; not composed. When Shadow pepper’s Badjohn Georgie with a “Niminimdiwh niminimdiwh idiggidimdiwh” in “Whop Cocoyea” or exclaims “Humni-anai-heh! Hamni-adda!” at the beginning of “Snakes” it is not because he put pencil to paper to conjugate the verbs “imi” or “humn,” but that the music told him to utter those ‘words’ on the fourth or ninth or seventeenth take at the studio in 2004 and 1984 respectively. And if the crowd at the tent in 2005 asked him to sing those songs only the studio way while he was up on stage, they would miss out on the “Widdiyimday widimmihimday wadaggihamdai” or “Oondee-yayai-heh! Omnee-yayao!” he might have given them instead when the music touched him that night. In fact, Shadow would not and could not accede to their stodgy wishes. That’s not how shadolingo works. The music and the mood produce it, direct it and send it sliding, whipping or careening into the world. But from where?

From its ‘extra-linguistic,’ and ‘para-symbolic’ dismantling of the building blocks of sensible language, shadolingo seems to both originate from and reach back towards something beyond. In artistic traditions that celebrate the primacy of the artist as author, improvisation is neither encouraged nor celebrated. While systematic experimentation and innovation are supported, even engendered within these composed arts as part of the process of learning, practising and mastering one’s craft, chance and ‘happy accidents’ are unwelcome.

Imposing one’s will upon the stone, wood, canvas or paper is elevated above the management of happenstance—even with the finest instruments and/or the finest materials. For to admit the author’s lack of control or dominance over his (the masculine pronoun is not just incidental here) materials and methods is to admit his partial or total failure as a great master. Inspiration, yes, accident, fortuity or intervention, no. Mastery but not mystery in their technique is what made Michelangelo and Mozart, Rembrandt and Chopin household words. Even Picasso, with all his obvious formal references to African art, was/is celebrated more for what his will did with/made of his (chance) encounter with “primitive” art. It was the same with Glenn Miller and other white bandleaders and their ‘domestication’ of that “race music” called Jazz.

Until Jackson Pollock and the other action painters of the New York School of abstract expressionism (i.e., flinging, dashing, pasting and scratching paint until ‘something’ told them to stop), and the developments in Jazz that had presaged and then accompanied “ab-ex” in North America (from old New Orleans Dixieland improvisation to Pharaoh Sanders Free Jazz), Western fine art had little place for chance and Nature’s co-authorship with man as he makes art. Western religions, particularly the Protestant churches and a great part of Islam, continue to struggle with the idea that God Himself might be playing dice with the universe (to paraphrase Einstein’s own Judeo-Christian anxiety on the topic) in processes like evolution.

Western classical music was composed by geniuses, then notated on paper, then played from there with a dash of the human spirit as befitting only the most expert musician—within reason. While musicians were allowed to add certain emphases here and nuances there, they dared not skip or add a note! The European peasantry could indulge in that savagery at their jigs, jotas and backcountry mazurkas but the music composed for assembled, well-dressed audiences would have none of that. The personal genius of the master composer was not to be subject to editing by some pisant harpsichordist or cello-come-lately at an impromptu fête in County Cork or Normandy somewhere.

This primacy of composition over improvisation demonstrates a fundamental difference between the fine arts of the West (and indeed much of the Global North) and the world beyond it. African, Amerindian and even classical Indian musics place far greater emphasis on improvisation[17] albeit to different degrees. And Amerindian and African musics especially have an abiding relationship with trance,[18] and even possession by music and rhythm.

Listening to shadolingo, it is no secret that Shadow is often in some kind of ecstatic state when he spits it—opposites like ‘sudden inspiration’ and ‘arranged composition’ collide during performance and elevate him into musical paroxysm. In that state, he is not just a master of inanimate instruments and acquired skills; he is a master of natural flows, waves, and cycles of sound. He is curating chaos (that mother of all creativity), determining its boundaries but otherwise allowing it to play out, express and manifest. As Khalil Gibran describes children,[19] so too music comes through Shadow rather than just from him. His mastery lies in polishing his craft and himself as instrument of that passage, as rudder of the “musical madness.” Art passes through everyone a different way depending on the degree to which they polish their craft and tune their instrument—the self being the instrument in question. This is why art is bigger than individual people and some examples of it get protected by UNESCO as our combined human patrimony—if enough of us concur that the work by an individual or a small subsection of us speaks of and to all of us.

Crossroads Vision 1, digitally manipulated graphite drawing. Lawrence Waldron.

In Shadow’s brand of mastery, he becomes the ladder, pole or potomitan[20] between the chaotic matrix of creativity and the ordered world of rhythm, tempo, melody, poetry etc. In the throes of shadolingo, he allows his role as author/composer/arranger to become dissolved into moderator/mediator/medium. Put another way, he ceases to push musical notes and syllables around like their boss and instead, lifts the lid/opens the roof on the crossroads and lets us glance at and listen to, for a moment, the swirling, blinding, deafening nursery of all ideas. The shadolingo issues forth, in short threads or long skeins. In Shadow’s music, we encounter more than inspired compositions; we glimpse creativity itself—if but for a few bars of music.

Can you imagine if all of Shadow’s music was pure shadolingo? The Calypso and Soca authorities would never have let him through the door at the Carnival competitions.

We can guess what Shadow’s mind-state is when he makes himself the axis mundi, uniting raw, awe-inspiring creativity and expertly arranged finished product. When he peppers us with shadolingo, even in our ecstatic response, we feel we’ve encountered something like this before. The Spiritual Baptists and Orisha practitioners give us some clue in their rituals and non-lexical utterances that Shadow might be on some kind of musical ‘moaning ground’ or singing out from some kind of zest or psychotropic, shamanic experience? Is he truly in a bass-induced trance when he sings phrases of shadolingo? What exactly is a trance anyway?

On this mundane side of the crossroads, where words are defined, even if ineffectually policed by schoolmarms (look how we were able to just make up the word “shadolingo” without being clapped in irons!), we like to make sure we’re using the right words when we talk about the word-shattering dynamics of shadolingo. Let’s get on the same page in the dictionary with regard to words like “trance” and “improvisation.”

The Oxford lexicographers define a trance as a “half-conscious state characterized by an absence of response to external stimuli, typically as induced by hypnosis or entered by a medium.” One wonders how they arrived at that “half” proportion. One also wonders whether the word trance can actually be applied to the state in which shadolingo is uttered or sung since Shadow must be more than just “half-conscious” to respond to the composed elements of the music in real time, and with such improvisatory aplomb no less. But as the dictionary offers up the etymological origins of the word, “trance” we seem to get closer to a description of Shadow’s mind-state during shadolingo. The roots of the word are closer to shadolingo than the word itself.

As it happens, “trance” was first used in Middle English, borrowed from the French verb, “transir” which means “to depart” or “fall into a trance” (perhaps we should put stress on the “fall” as verb), and the French usage, in turn, derives from the Latin verb, “transire,” which means “to go across.” Now, we get a far more accurate image of Shadow in transit between states, transcending linguistic, cultural, mental and phenomenological boundaries to arrive at pre-lexical vocalisations, and transmitting through our speakers the pore-raising experience of that crossroads liminality. As we go back in time, stripping “trance” of its nineteenth-century freight of hypnotic influence, mummy-unwrapping parties, table-top seances and other Victorian parlour games to the pre-Imperial roots of the word, we find a more universal meaning that might apply to shadolingo. To be in trance is to transcend.

Field recording of the Maroni River Caribs of Surinam, “Shamanic Ritual: The Dance”

There is a fairly large body of research on the link between music and trance, especially as employed by shamans and other ritual specialists.[21] In fact, music is known to be one of several ways one can enter a trance or trance-like state. Repeated or rhythmic motions, including repetitive recitations, chants, singing and instrument-playing can cause the participant in such activities to become entranced.[22] Indeed most music depends on repetition to hold its form and that repetition triggers anticipation, participation and hypnotic effects.[23] Of course, the other means of attaining trance is through the use of psychotropic substances. Our Amerindian forebears were adept at both these methods, sometimes using them together, and their traditional arts and music give evidence of this.

Images of the Arawakan behique (shaman) in Taíno sculpture and ceramics. These examples are from the island of Hispaniola and represent the shaman (a and b from left to right) as the entheogen first takes effect or exhausted after it wears off; (c and d) in the depth of the visions brought by the drug (cohoba).

All of these techniques, from strenuous repetitive dances to sonorous and irresistible rhythms and melodies to sniffed, snorted and ingested entheogens (formerly known as “hallucinogens”) have been used by ritual specialists throughout history to achieve altered states of consciousness, to communicate with the dead, the gods, the indescribable fabric of the universe, and then return with vision, prophecy, wisdom.

Shadow’s method of crossing over has always been music—“give me muuusic!” he insists in “Don’t Try Dat” (1978) to a wealthy lady trying to bribe him off his ethereal musical perch. Music supplies the pounding rhythms from drum and bass that drag us down through the floor. It exalts us with the melodies, themes and chords that return, repeat and vary, sweeping us along. Then the shadolingo comes and ‘all fall down!’ We feel as if we have left our sweaty flesh to pound and stomp the earth, while we reach into the noumenon. No instruments were ever constructed to so faithfully produce repetition as the electronic ones. And they have served Shadow well in his quest to reach for the cosmic. Since the 1970s, sounds can be digitised, sequenced and looped to infinity but also endlessly manipulated and varied to surprising and downright mystical effect. As such, after the skin drums and ideophones under a starry sky, there are few kinds of music more entrancing than electronic music.

What of the word, “improvised”? Here, in the realm of decipherable words, how might we define “improvisation” before trying to apply it to shadolingo? Does the dictionary definition of that word allow Shadow to be more than “half-conscious” as he straddles the musical eternal and the finite structure of a recording? From the Latin root, “providere,” meaning “to make preparation for,” the English verb “to improvise” (i.e., with that antonymic prefix “im” in front of it) means “to create and perform (music, drama, or verse) spontaneously or without preparation.” There is no variance here, contemporary or ancient, between shadolingo (or Calypso extempore for that matter) and the intended English, French or Latin meanings of “improvise”/“improviser”/“improvvisare” respectively. Thus, the lexicographic origins of “trance” and “improvisation” both apply to the practice of Shadow’s in-the-moment para-lexical lingo.

Singing Sandra’s “The War Goes On” (early 2000s)

It is both in the slippage from the self that is part of trance, and in the lightning-fast reflexes of improvisation that shadolingo pours through its sole exponent, the Shadow. No other Kaisonian does it, although, on occasion, you might catch Duke, Singing Sandra or others briefly doing something similar and comparably powerful (as in the last minute of Sandra’s “The War Goes On” or between the verses on her “Ancient Rhythm,” 2003). Yet, trance and improvisation would seem to be opposites since the former causes you to lose yourself (often through repetitive motions or vocalisations) and the latter requires you to be supremely present in the moment (looking out for, interacting with, and causing changes in the composed music).

Gnawa music brings people into trance during the Lila ceremony, Morocco.

Moreover, you can use music to achieve trance in two major ways, and these ways too are virtually opposite—droning and improvisation. In droning, the repetition is what ironically lifts you out of the humdrum into that serene but sometimes adrenal zone that experienced meditators and runners speak of. An Indian tambura chimes behind the sitar lifting you to heights above the paisley brocade of an evening raga. The chants of the Malian-Moroccan Gnaoui/Gnawa singers pulse atop hectic tbel drums whipping you into a mental frenzy before punching through your fever or spirit possession.[24] The crystals inside an Amerindian shaman’s shakshak (maraca) swirl and swish like the accelerated winds of a hurricane or the heartbeat of your mother as you curl in the calabash of her uterus. In all these cases, droning repetition unzips your mind and subsumes or subverts your regular routine with a new, feverish one. The goal is often healing, forcing you to leave your body or mind before returning you to a restored version of it.

Now imagine what happens when improvised vocalisations like shadolingo join that already elevated state. This is why words that make no sense can speak truth, can impart wisdom and well-being.

I know yuh singing nonsense,

But yet ah love yuh nonsense.

Is obeah!

Yuh wokin’ obeah!

…yumooneeyuyh-amooneyuyoi!

—“Obeah” from Return of the Shadow (1982)

“Obeah,” from the album Return of the Shadow (1982)

At the crossroads, opposites like sense and nonsense, meaning and meaninglessness, icons and iconoclasty, regularity and irregularity, the repetitive and the improvised, the self-aware and the selfless meet and get stacked up on top of each other like lenses. The order of that stack determines whether we get laser focus, refraction or broad dispersal of psychedelic sounds.[25]

In this paradoxical, liminal mind-space at the crux of language and music, the lenses of melody and rhythm ultimately subsume those of linguistic meaning. The conventions of human language refract into shadolingo. As the eternal comes pouring out the human voice, an instrument usually used for language, nonsense makes perfect sense as music.

Despite its antagonism to the conventions of spoken language, shadolingo’s communicatory function makes it as much a language as music.

Crossroads Vision 2, graphite on watermarked envelope paper. Lawrence Waldron.

What Shadolingo For?: Shadolingo Does…

We define shadolingo, trace its use across time, and then pore over the European etymologies of “trance” and “improvisation” to make sure we’re thinking straight about the source of these para-lexical utterances. But is shadolingo just an abstract, made-up musical category or does it do something? It’s already clear that one of the functions of shadolingo is to bulldoze the semiotic structure of language to use its building blocks (i.e., vowels, consonants, hisses, stops etc.) instead for purely musical expression. Another function of shadolingo is to unshackle the singer and the listener both from history and restore them to a state of mental and emotional freedom.

The “longing to be free from the psychological and cultural freight of language” mentioned much earlier in this essay does not specify which language. Well, first, I am of the opinion that if Shadow grew up speaking Inuit, Igbo or Telegu, he would have still broken down into shadolingo. So, the short answer is, “all language.” But in the immediate wake of the Black Power years in Trinidad & Tobago, in which pan-Africanism was driving the sound of the new Soca musical idiom; when Duke’s “Black is Beautiful” (1969) was sung with pride and a deceptively conservative-sounding Chalkdust commented that young people were still “colour crazy, in fathead and daishiki,” with some talking about returning to Africa or India (from “We is We,” on the 1972 album, First Time Around)[26]; when Trinbagonians put up their rainbow of fists and put their hard West Indian “t” in the Black American saying, “Right on!”, the language to throw off was English. It didn’t seem to completely jive with the rhythms of Afro/Indo-diasporic music.[27]

Shadolingo, when it first broke out, demonstrated a dissatisfaction with European-derived lyrical and musical conventions. Even the heavily Africanized, Indianized, Celticized maritime forms of these that we speak, sing and perform in the formerly British West Indies seemed to be lacking some…essence. Given our position here at the Shadowlingo blog on Shadow’s vital role in the early development of Soca, many of us would add to this anticolonial linguistic dissatisfaction, and outright rebellion against English, the throwing off of the musical structures of 1960s-style Calypso, which had been dominated by dashing, metropolitan Sparrow and the returned Londoner, Lord Kitchener.

Language is not the same as culture. The fact that we speak English doesn’t make us Brits. But every language carries a massive cultural freight that shapes the minds of its users. Our Midnight Robber is more likely to quote Shakespeare than Voltaire or Valmiki. Many of us know more about Robin Hood and even Dick Turpin than we do the exploits of Mansa Musa or the Taíno culture hero Deminán Caracaracol…even though we are living on Arawakan land in black and brown bodies. It is not just because our ancestors were physically colonised by the British that we are carrying countless British cultural and mental habits, although that physical conquest more fully explains other aspects of our culture, from our economic to political systems. It is also because the British imposed upon and then left us with their language as a vector of their culture. Our anglicisation (and Anglo-Americanisation) continues through this language.

As regrettable as this is, I personally don’t stay up at nights mulling it over. Because it is too much spilt milk to cry over. It is, in fact, an ocean of milk and requires a boat (or a strong stomach),[28] not tears. Across Africa itself, Arabic, French and English are the most common national languages,[29] thanks to comparable colonising processes there. It’s not as if we can go back to Africa (or India) and be baptismally/Gangetically restored because over there too, culture is forever changed by Europeans (and Middle Easterners).

Yet, from their Bantu loan words (like “tote” and “nitty-gritty”), neologisms (not least of which is “dreadlocks”) and trendy slangs (from “hepcat” to the derived “hipster”) to their grammar, African Diaspora people especially have had a greater effect on the English language than any other non-Europeans.[30] To say “big big” to mean “very/truly big” is to apply West African syntax to an Anglo Saxon language. And when the whole world says, “okay,” they seldom consider that they might be speaking Mande.[31] Black and brown people have made English their own, from Jamaica to Jaipur. So, while the English language has shaped and confined our minds in many ways, we have, in turn, reshaped both local and world English(es) to reflect our folkways and thought patterns.

No island of the Caribbean has more different kinds of English than Trinidad, with its cosmopolitan population filtering the lingua franca through Kikongo, Yoruba, Hindi, Chinese, Lebanese and Syrian Arabic, French, Portuguese and Spanish grammars, feelings, logics, and other structures. Yet, as mentioned above, even those multiple Trinidadianisations of English are inadequate for Shadow when he reaches back to his roots. For Shadow, Africa was the oldest part of himself that he could find, offering the idioms closest to music’s shrouded, roiling core, and in musically induced trance, he fell back on constituent syllabaries derived from the languages betwixt the Congo and the Bight of Benin. Yet, he was reaching for a mother tongue even more ancient than those. ‘Mixed up well, And poured in party’[32] the right liquified vowels melodiously swirling together, the right pre-linguistic consonants pulsing outward from his chest to his vocal cords, could send him and us back to “Nature’s cradle,” still rocking and making new galaxies.

Even with its Bantu love of long m’s, n’s and bouncy syllables, shadolingo is not just reaching for lost African languages bred out of us by the French and British, but to a place beyond and before language itself. It stretches through (not past) Africa, towards something more fundamental, more pre-cultural, more cosmic in the nature of sound itself. This might make it sound like it springs from some primitivistic urge,[33] but its close coupling with electronic music (as exhaustively proven above) makes shadolingo a language of the eternal and fundamental, rather than of the undeveloped beginning. The lingo is not just chronologically “before” but conceptually prior. And it is this reaching for the fundamental that urged Shadow to mash up language into phonetic modules, vocal building blocks so it could better serve music.

Shadolingo in Retrospect

In 1973, Shadow walked into Semp Studio, looked at the band and broke them down in his mind, considering guitar, brass, drums/percussion and bass separately. With these component instruments of Calypso thus arrayed before his mind’s eye/ear, he decided to speed up the horns, shuffle the priority of the instruments to put the bass on top and, while the bass was playing the rhythm instead of the drums, he insisted it not play on the beats but mostly between them. The bass was the call and the beats were the response! What?! On a song called “Bassman,” after just three bars of four beats each, the next bar seemed to spiral out of control, downward through the thickening strings on the bass guitar.

Tum pee dim pom—pom (4 beats/5 notes of onomatopoeic proto-shadolingo)

Bpum pee dim pom—pom (4 beats/5notes)

Bpum pee dim pom—pom (4 beats/5 notes)

Tim tim tim tim tom pom pom pim pom pim pom pom (6 beats/12 descending notes)[34]

Should we follow the beats or the bass? Musicians and Carnival revellers alike decided—the bass! We lost track of the bars but never the bass, and yet somehow still kept the beat. It’s a good thing we weren’t thinking about it at the time. We might have tripped over ourselves and tumbled in the madding crowd.

Shadow had returned to fundamentals and out of that core had reinvented an increasingly staid Calypso music. And after we finished prancing, we asked ourselves “Wait! Whah jus’ happen dey?”

Two years later, encouraged by the success of his syllabic calling out of Farrel’s bass notes in “Bassman,” Shadow did the same on “Constant Jamin”

Wim dim wim pim pim pim

Pim dim wam wam tam-pahm

Listening to himself ape the bass, he decided to go deeper. Like Wassily Kandinsky seeing his painting laying on its side, liking it that way and wondering why a painting always had to be a picture per se,[35] Shadow wondered why a syllable always had to make a recognisable word or imitate another instrument. He ruminated on the human voice and broke it down into composite sounds. But this decision wasn’t shrewd and strategic like putting the bass on top the music had been. This session of young Shadow’s master class in ‘Back to Basics’ would be about improvisation, informed by instincts almost beyond his own control. When it came to his extempore utterances, he would let Nature take the wheel…and his vocal cords.

The resulting shadolingo took only two years to develop from catchy onomatopoeia on “Bassman” to a mature and distinguishing mode of vocal expression on “Constant Jamin’.” Two years from an idea to a full-fledged musical philosophy.

In his experiments with electronic sound, Shadow yet again, broke music down into composite noises—into ones and zeros, in fact. And from those digital building blocks, he reconstituted Kaiso yet again in the 1980s and ’90s. Ironically, few instruments better support the cosmic origin and vision of shadolingo than synthesizers. In his experiments with and transitions to electronic music from the 1970s to 2000s Shadow seems to have been seeking an instrumental scaffold along which his otherworldly compositions, lyrics and shadolingo could climb into the world.

In turning our bodies over to these machines in Shadow’s employ, had we surrendered our trembling souls to cold technology, or had we surrendered our writhing but ageing bodies to the cosmic clockwork that the machines denote and connote in their digital, atomic fundamentalism? The abstract question lingered only for a moment, before “Poverty is Hell” or “Stranger” swept it away like an inconsequential dust mote on a polished dance floor…and we transcended.

Shadow’s constant return to the centre of the crossroads has never been out of a longing for simplicity, and definitely not for restoration to some sylvan or ‘primitive’ past. It has always been out of fathomless creativity, and an unending quest for (and receptivity to) new ideas. Not mere novelty (i.e., coolness) or vainglorious resurrection (to rejuvenate his career) but a proven theory of sustainable renewal. Shadow restlessly composed music all his life, at all hours of the night and day, in dry and wet and stormy seasons of life. This restlessness bid him to invent what had never been heard before and to renovate what had. It was in his explorative search of music that he circled back time and again to its mysterious core. And from this axis, he came back to us every few years, like a prophet down off the mountain, with new sounds and innovations in instrumentation and vocality. If we are just ‘fans’ we will praise him as the lone voice at the crossroads, chanting in his own language. If we follow his example, however, we will search out our own centre and find our own voice as persons, and as a people.

Epilogue: Shadow, the Kaisofuturist

While preparing her recent memorial article on Shadow, journalist Erin MacLeod asked me several important questions about this towering Kaisonian and his legacy. I did what I could to answer intelligently in the limited time we both had. In the course of our back and forth by e-mail, MacLeod also made passing reference to whether Shadow might be considered an Afrofuturist, to which I never responded. It is not that I had never considered this question before. In fact, in my private reflections I have often compared Shadow not only to the ‘Mad Monk, Thelonious’ as I call him (pre-Afrofuturist, certainly, but carrying the gene), but also to Sun Ra, the original Afrofuturist musician/composer/performer/mystic/philosopher-poet.

But I demurred to call Shadow an Afrofuturist. Shadow’s persona has always been chromatically and symbolically black, and culturally pro-Black, but not primarily concerned with Blackness or any other kind of identity. And, while he is some kind of futurist—definitely a Kaisofuturist, in light of the visionary use of electronic instrumentation he introduced and shepherded—he is not just an Afrofuturist. Alongside his use of black as philosophical antipode, Shadow has always earnestly explored himself as both finite individual in the “aging system” and as “cosmic baby” in the grand scheme. He has done this while also placing himself and his music beyond the reach of the shifting alliances, affiliations, and temporal considerations between the microcosm and the macro cosmos.

Expanding from MacLeod’s question, Shadow was the consummate outsider, belonging to nothing (except his own tent both figuratively and physically at the 1970s Master’s Den), but both dread individualist and loving universalist at once. He was far less interested in blackifying the scriptural past or the digital future than in considering the paradoxes of both culture and nature overlaid (e.g., the cock and the farmer in “Cook Curry and Crow” are both victim and perpetrator, in both natural and cultural forms of predation). He always saw the internal contradictions, ironies, similarities, grotesquery and beauty of structures and systems. And in the last decade of his career, he was particularly interested in overlaying the technological with the organic as horns and drums re-joined the digital instruments.

An odd thing stood out to me at the various memorials for this outsider in the hours and days before and after his funeral—the way in which the different camps came out to praise Shadow’s name and claim him, when in fact Shadow was not a true member of any of their respective coteries. Race, religion, political parties, credential-granting institutions are all local, temporal concerns that Shadow might have referenced (and not always complimentarily) but none were anywhere near the core of Shadow’s raison d’etre.

The old Black Power activists from the seventies have always embraced Shadow because of how he himself presented and performed Blackness in the face of that brown-skinned metropolitanism that dominates post-Independence Trinidad (more than in Tobago), from the halls of government to advertising billboards. But Shadow has never been just concerned with elevating African or Black identity.

At one memorial, I was glad to hear some Shadow aficionados grumbling audibly about hypocrisy during some of the evangelical prayers and speeches given in Shadow’s remembrance. For when a singular Christian pastor delivers funerary benedictions over Shadow’s body, in the absence of a Hindu pundit (Shadow has massive Indo-Trini fans!), Muslim imam (especially one of the progressive ones we have in Trinidad), and when not even an Orisha spiritual leader is invited to speak as befits our plural society, I wondered if this singular pastor was familiar with Shadow’s oeuvre and the fact that his songs never mention Jesus or even “God.”

In his music, Shadow often praised Nature instead (like in “My Vibes are Heavy”) and seemed to believe in a kind of natural Creator, which he never presumed to describe but which he references in the effulgent “Hills Over Yonder” (B-side of the 1978 single “Something Wrong”) and “Music (Dingolay).” To hear Shadow exasperatedly utter “What more yuh want? Aahhhh Lord!” at the end of “Sing Boy Sing” (2004) is amusing in that, given his lack of songs crying out to God to “put a hand” as we say, that “Aahhh Lord” is obviously an idiom (like “Oh gorm!” or “Oh shit, man!”) used for emotive effect. “Aahhh Lord” is the closest Shadow ever came to mentioning anybody’s God by name. He was obviously not an atheist; he just didn’t believe in the isms that wrack Trinbago with schisms.

“Sing Boy Sing,” from the album Fully Loaded (2004)

In the same way that this transcendent Shadow has never pledged allegiance to any particular deity in song, he has not supported any political party, and has likewise never identified with any contemporary construction of “race” beyond inhabiting his negritude without shame and wielding it as an axe to open the ontological cracks in metropolitan creolité/creolity/mestizaje.

Shadow never told all these groups, “No, I am not with you” but as they all rushed to stamp his coffin like corporate sponsors, I was possessed of a burning urge to disabuse them of their folly. Rather than startin’ to cuss like Rufus in “Doh Mess wid Meh Head” (1979), I am doing it here on Shadowlingo. Steupps!

Shadow’s is the true “every creed and race” philosophy enshrined in our national anthem, not the Christocentric, honey-brown tyranny of the majority that gives fatigue to dark-skinned Blacks and Indians about their “Madras” and “tar baby” blackness, decries their polytheistic savagery, assumes fifth-generation Chinese Trinidadians are foreigners before they even open their mouths, or presumes everybody knows and wants to recite the Lord’s Prayer at the commencement of public events.

With his ‘live and let live’ attitude, the Shadow, now dubbed “Dr Winston Bailey” by the University of the West Indies, who spent so much of his life ideating, experimenting, suffering, innovating on the periphery of the Trinidad music establishment was, perhaps not ironically, one of our republic’s best citizens. But he was never one for membership in movements, parties, committees and such. Soca came and acknowledged him as a member, granting him admittance to a movement that hardly recognised he was one of its very progenitors. Imagine that! In the end, Shadow’s ‘membership’ in any demographic was/is a matter of resemblance; not subscription. Shadow always doin’ he own t’ing.

Endnotes